Key takeaways

- Diverse, nimble and connected to consumers — these traits characterize local and regional food systems (LRFS).

- Demand-driven innovation led to booming online LRFS sales during the summer of 2020.

- Small food processors quickly hit capacity when larger plants’ output slowed due to COVID-19.

- Pandemic-driven policy innovation in LRFS could drive broader regulatory reform, but the limitations and vulnerabilities of an over-reactionary response should be carefully considered.

COVID-19 elevated U.S. food access, affordability and supply chain issues into media, industry and policy discussions during 2020. Known for their short supply chains and locally focused marketing, local and regional food systems (LRFS) nimbly responded to marketplace needs and connected to customers during the pandemic. As LRFS have become more visible and accessible, some food buyers and policymakers have recommitted to supporting and sustaining such food systems. Because local food sales grow when the economy grows,1 the recession that began in 2020 may impact LRFS sales disproportionately.

This research-based guide summarizes how LRFS, including producers and processors who participate in these systems, innovated during the pandemic to respond to market demand changes, and it considers policy changes that may benefit the sector’s future.

Local and regional food systems and food processing prior to COVID-19

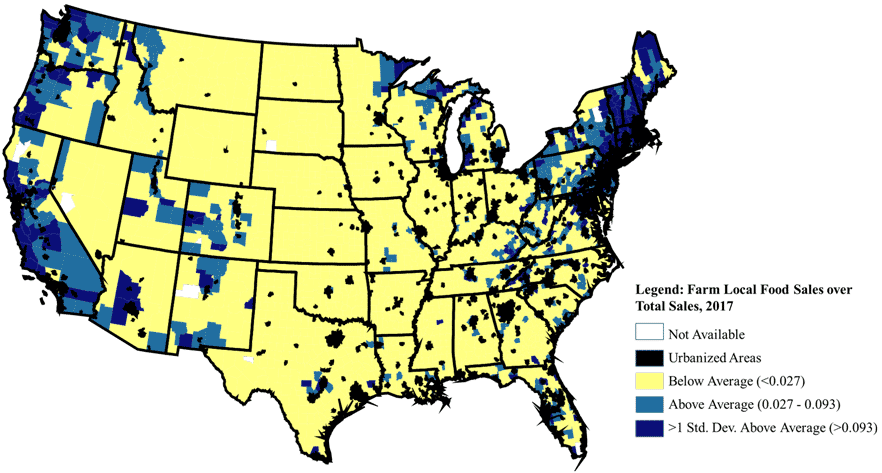

LRFS farm sales totaled $11.8B in 2017 — only 3% of total U.S. agricultural production and food sales — and just 7.8% of U.S. farms participated in LRFS, according to the 2017 Census of Agriculture. Pre-COVID LRFS sales concentrated on the coasts and near major urban markets (Figure 1).

Missouri’s LRFS sales totaled $70.7M or 0.67% of total agricultural production. Direct-to-consumer sales were conducted by 3.8% of Missouri farms, and 0.7% of Missouri farms sold food or regionally branded products directly to retail markets, institutions and food hubs.

Like LRFS farms, many food and beverage manufacturers are small-scale and target regional markets and buyers. Research summarized in MU Extension publication DM103, Agricultural and Entrepreneurial Factors Driving U.S. Food Manufacturing Startup Locations (July 2020) suggests areas with high LRFS activity also recorded growth in small food and beverage manufacturing — at least, pre-COVID. It will be years until these data are available for the COVID era. Although some types of food and beverage manufacturers grew in the past 15 years, others declined. For example, the U.S. had 7% fewer small animal slaughtering and processing facilities in 2002 than in 2017. This decline may have worsened the disruptions felt when larger plants faced COVID-related slowdowns.

Figure 1. Local and regional food sales as a share of total farm and ranch sales. (Source: 2017 Census of Agriculture, graphic from Thilmany et al., 2020)

Online sales as an alternative to face-to-face sales

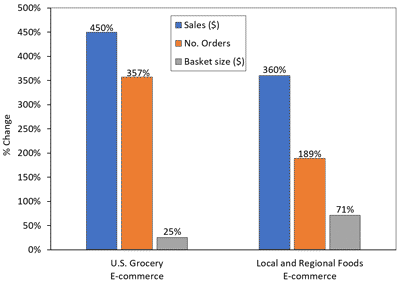

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, 33% of U.S. households shopped for groceries online in May 2020 compared with 13% in 2019.2 E-commerce sales growth was not limited to grocery stores; local and regional food operations also pivoted to e-commerce.

Figure 2. Changes in online food shopping amid the COVID-19 pandemic, 2019–2020. (Source: Graphic from Thilmany et al., 2020)

Figure 2. Changes in online food shopping amid the COVID-19 pandemic, 2019–2020. (Source: Graphic from Thilmany et al., 2020)

Aligning with the broader online grocery trend (Figure 2), online sales by LRFS operations bloomed. Using semi-structured interviews with 10 e-commerce platforms that served LRFS in May 2020,3 we found online local food sales increased by 360% between April and May 2020 due to increases in orders (+189%) and dollars spent per order (+71%). One respondent indicated a consumer may have only spent $10 to $20 per transaction at a farmers market but would spend $75 to $100 in online transactions. Historically, few farms — only 8% of farmers with direct-to-consumer food sales in 2015 (MU Extension publication G6224, Could Online Sales Be a Direct Marketing Opportunity for Rural Farms?) — have maintained online marketplaces, so this expansion could be an important long-term trend to track going forward.

Web traffic to e-commerce platforms also increased significantly (+247%).4 Resources such as access to broadband, e-commerce extension education, technical assistance from community groups and commercial e-commerce platforms helped producers and consumers adapt and respond to changes in food marketing.

Meat processing bottlenecks created interest in diversifying supply chains

Beyond farms, locally and regionally branded food processors faced significant supply and market disruptions at the beginning of the pandemic. Small animal slaughtering and processing businesses often operate as custom-exempt5 facilities and serve truly local markets (often within the state). The number of small processors with fewer than 20 employees has dwindled — 7.3% fewer in 2017 relative to 2002.1 Operational small-scale processors quickly hit capacity when demand spiked as large plants closed or reduced their capacity due to COVID-19 infections among workers.

In response to animal production system bottlenecks and short-term consumer price spikes, federal policymakers witnessed renewed interest in promoting a more diversified supply chain and permitting state-inspected6 meat sales across state lines. In the absence of federal action, several states with their own inspection programs (e.g., Wyoming, Oklahoma and Nebraska) lobbied for relaxing federal rules and proposed changes to their own regulatory policies. Similar to Kentucky, Colorado and Montana, Missouri provided grants to support meat processors. Funded by $20 million in CARES Act dollars, Missouri enabled facilities with fewer than 200 employees to apply for grants.

Looking forward: will COVID-19 catalyze permanent food policy changes?

Out of necessity, the pandemic spurred LRFS policy innovation at the federal, state and regional levels. Examples include the following:

- Federal and state governments “flexed” a number of regulations to respond to the most visible “pain points,” such as retail label requirements for foods destined for wholesale.

- USDA temporarily extended the expiration date of audit certifications for Good Agricultural Practices and relaxed some of the requirements of the Food Safety Modernization Act’s Produce Rule.

- On the consumer side, many school districts and farm-to-school networks incorporated local foods into emergency feeding programs during school closures.

Following the pandemic, policymakers may revisit and reform a broader set of food regulations rather than simply reverse current exemptions. For example, what might happen if they loosen food safety requirements for locally produced and processed foods sold within local markets? Cottage food laws, which allow small-scale food entrepreneurs to produce low-risk foods in home kitchens and market them via direct-to-consumer outlets, largely eased in the past 10 years. Changes to these laws illustrate that sensibly relaxing food regulations can lead to more businesses.7

When faced with calls from advocates to overhaul the food system, policymakers must balance such proposals with a realistic look at the limitations and vulnerabilities of an over-reactionary response. Shorter, less centralized supply chains may lead to higher productions costs, and forced product differentiation (e.g., mandating cage-free eggs) can result in higher prices for consumers.8 Policymakers might carefully consider the market demand for more niche meat processors, for example.

Source

- Thilmany, D., E. Canales, S. Low, and K. Boys. “Local Food Supply Chain Dynamics and Resilience During COVID-19.” Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy. (forthcoming).

Endnotes

- O’Hara, Jeffrey K., and Sarah A. Low. 2016. “The Influence of Metropolitan Statistical Areas on Direct-to-Consumer Agricultural Sales of Local Food.” Northeast Agricultural and Resource Economics Review 45(3): 539– 562. (2016).

- Brick Meets Click. U.S. Online Grocery Continues to Set New Records -$6.6B in Sales for May 2020 (PDF). News release, May 28, 2020. (No longer available online.)

- This information was obtained through a series of 10 interviews conducted with e-commerce platforms used by LRFS firms in May 2020. More information on this research, conducted by Dr. Canales, is available in the underlying research article.

- Although traffic may not always convert to sales, it likely demonstrates an increased interest in online local food options; more visible platforms are easier for customers to find and use.

- A custom-exempt meat processor is not required to have continuous inspection because they only process meat for the owner of the animal. The meat or poultry cannot be sold and can only be consumed by the animal’s owner, owner’s family and their non-paying guests.

- State-inspected meat processors must enforce requirements “at least equal to” those imposed under Federal laws. The big difference is that, product produced under State Inspection is generally limited to intrastate commerce.

- O’Hara, J., M. Castillo, and D. Thilmany. “Do Cottage Food Laws Reduce Barriers to Entry for Food Manufacturers?” Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy. (forthcoming).

- California’s animal welfare laws, which force everyone to practice what some consider niche production practices through regulation, can result in higher prices for consumers and welfare losses. Mullally, C. & J.L. Lusk. “The Impact of Farm Animal Housing Restrictions on Egg Prices, Consumer Welfare, and Production in California.” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 100(3):649–69. (2017).

This guide was supported in part by Enhancing Rural Economic Opportunities (NE1749) regional research committee with long-term support from USDA NIFA.