In rural communities with low natural amenities, population decline has frustrated rural leaders and jeopardized community resources. Previous research suggests migration to low-amenity rural areas is primarily driven by social ties, rather than economic opportunities.

This publication highlights findings from a recent MU Extension study that investigated attitudes on rural living preferences among northwest Missouri residents. Rural leaders in the study region provided the impetus for this investigation as they sought to receive input on how to attract newly footloose workers. The study found that motivators for migration to rural areas include social ties, community attachment and employment opportunities. Understanding motivating factors for migration helps guide community leaders in proactively attracting and retaining new residents to depopulating, low-amenity rural areas. Additionally, insights can be leveraged by policymakers as they encourage population retention and growth in rural communities.

What impacts migration to rural areas?

Migration patterns are critical to population growth and the future vitality of rural communities across Missouri. The United States has experienced ebbs and flows of growth in rural areas for decades — communities with natural amenities and proximity to employment centers were more likely to attract migrants and foster vibrant rural communities. Natural resource extraction, employer location decisions and urban expansion have also impacted the urban-rural migration flow.

In addition to external factors, individual motivators and characteristics drive migration into, and out of, rural communities. Studies on rural migration suggest that a lower cost of living, family or social attachments and previous experiences of living in rural areas motivates some rural migration decisions.

Examining low-amenity rural areas specifically, researchers posit that return migrants are likely attracted to these communities due to family and place-based ties. Return migrants are of particular value to rural community leaders due to their likelihood to return to low-amenity rural areas and their contributions to social and economic vitality. Returners can bring an infusion of new ideas and experiences back to their communities.

Motivators for migration are complex

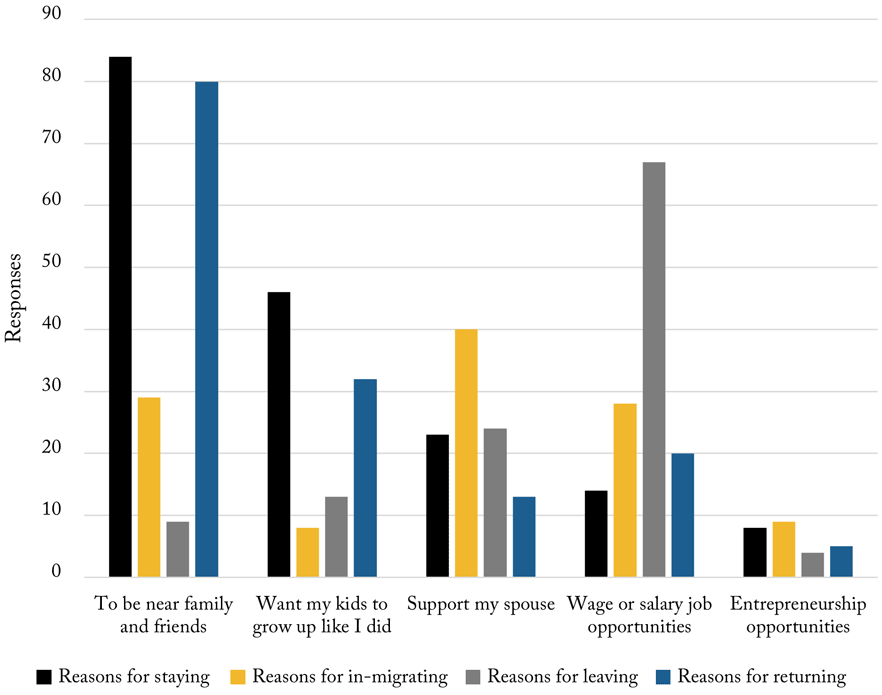

MU Extension researchers found that motivations for migration vary among individuals in northwest Missouri. Wage or salary job opportunities, along with educational opportunities, were common motivators for individuals to leave rural areas; another common motivator for migration was educational opportunities. Conversely, employment opportunities including entrepreneurship and business ownership were commonly cited motivators for Stayers and In-Migrants to remain in, or return to, rural areas.

This study also found that non-economic motivators drive migration decisions. The strongest motivations for staying in the region included proximity to family and friends, raising children as they were raised, and the ability to engage in their community. This indicates respondents placed household and family needs first when making decisions. Returners were more likely to be motivated to be near family and friends; a secondary motivation for this group related to wanting their children to grow up like they did, indicating a nuanced attachment to place that likely includes community structures, rural lifestyle, and educational institutions. Return migration to rural areas is most likely among young families and younger retirees.

As a whole, individuals make migration choices not only for themselves but also as households. In-Migrants more frequently identified a household rather than individual consideration, and there was a split between household and social consideration.

Tools for rural communities

This research reinforces the importance of community attachment and inclusivity in rural communities. Results from this study suggest that individuals with specific characteristics are more likely to migrate to low-amenity rural areas, and practical applications for recruitment efforts can be implemented by community leaders.

Targeted recruitment of self-employed entrepreneurs (along with early retirees and households with children)may be more successful than broad advertising. Self-employed individuals may be the most open to living in a rural areas, and in a rural community, each entrepreneurial family that moves in can make a palpable difference. This study suggests policy recommendations for attracting entrepreneurs as return migrants to rural areas may be worth consideration.

Communities that deliberately engage in-migrants and return migrants to build a sense of belonging may be more likely to retain these migrants through periods of economic and social stress. For example, communities can use many low-cost approaches to increasing population retention if they have strong local institutions and organizations. Some ideas for fostering strong community attachment among in-migrants and returners include:

- Work with real estate agents and others to form welcoming committees that identify and adopt new families.

- Schedule short periodic visits with new families and use this time to listen to their questions and then talk about key community assets.

- Work with schools to develop new family onboarding policies that encourage children and parents to join school clubs.

- Create leadership positions in civic committees that must be filled by new or returning residents to ensure a plurality of views and perspectives are heard.

Rural communities can help in-migrants build stronger networks and strengthen their social capital which is likely to lead to stronger community attachment (or a sense of belonging). In turn, when people feel connected to their community they are more likely to become involved and contribute to further enhancing the community.

Additional resources

This extension publication is based on peer-reviewed research published in 2022: Sarah A. Low, Mallory L. Rahe, and Andrew J. Van Leuven. 2022. “Has COVID-19 made rural areas more attractive places to live? Survey evidence from Northwest Missouri,” Regional Science Policy & Practice, 1-21.

This publication was supported by partner contributions from The Community Foundation of Northwest Missouri’s Maximize NWMO Regional Vitality Initiative. Funding for this publication’s analysis is from University of Missouri Extension with long-term support from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Institute for Food & Agriculture.