Soybean cyst nematode (SCN) is the most devastating and yield limiting pest of soybean in the U.S. including Missouri. A recent three-year study done in the United States estimated that soybean cyst nematode (Heterodera glycines) caused annual losses of $1.286 billion (128.6 million bushels).

It is often difficult to identify fields with SCN infestations becauselow numbers of SCN will cause little damage to roots so above ground plant growth and appearance may be normal (Figure 1). Stunting of plant growth, visible changes in leaf color and wilting, and yield loss will increase as the infection of roots by SCN increases.Yields may decrease slowly for a number of years as the population of SCN increases in the soil and infection of roots increases. Suspect fields usually have plants of different heights, but environmental conditions may make stunting less obvious.

When SCN is present and plants are under stress, symptoms such as chlorosis (Figure 2), plant stunting, and (in extreme cases) plant death can occur. However, these indicators are similar to those observed with other crop production problems such as nutrient deficiencies, herbicide damage and drought stress.

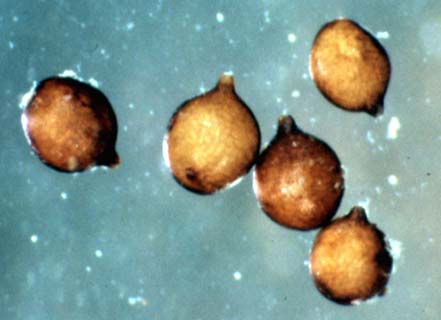

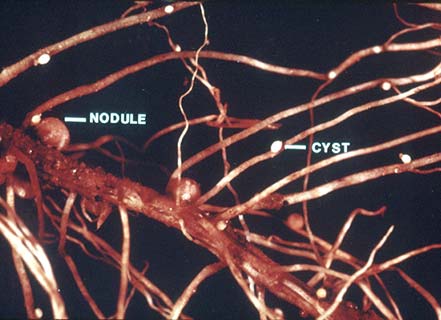

White (or yellow) females on roots are the only visible sign of SCN infection (Figure 3), and these are most often observed 4 to 6 weeks after soybean emergence. Plants exhibiting chlorosis or stunting can be dug in the field and the roots examined for the presence of white females or young cysts on the roots.

Many fields in Missouri and other midwestern states are now farmed under reduced tillage. Numerous studies have been conducted in Missouri and other states on the effects of minimum tillage on soybean cyst nematode. Lowered numbers of SCN eggs have been observed in some studies, but the decrease in eggs was not dramatic enough to adopt minimum tillage to manage SCN. Soil erosion management is a much better reason to adopt minimum tillage.

The most accurate way of determining whether SCN is present in a field is to have the soil tested in a nematology lab for the presence of SCN eggs. Sampling efficiency and laboratory cyst extraction are not 100 percent effective, however, and a significant number of SCN eggs need to be present in the soil for lab detection.

Note

Do not rely on visual inspection for diagnosis, because once the cysts have matured, they turn brown and fall off the roots.

Life cycle of the nematode

Nematodes are one of the largest, most diverse groups of multicellular organisms and are second only to insects in abundance. Nematodes are animals that have a wormlike appearance. Most nematodes are beneficial organisms that help decompose organic matter, releasing nutrients for plant uptake, but a few attack plants.

The number of juveniles entering the plant root soon after plant emergence can have a dramatic effect on plant growth and development. Plant damage occurs from juvenile feeding, which removes cell materials and disrupts the vascular tissue. In short, SCN infection inhibits the growth and functioning of the soybean root system, interfering with nutrient and water uptake. SCN infection can also reduce nodule formation by nitrogen-fixing bacteria and can increase plant damage when other plant pathogens are present in the soil.

SCN and resistant soybean varieties

In the past, an SCN population was given a race designation by comparing its reproduction on a set of four soybean germplasm lines with that on a standard SCN-susceptible soybean cultivar. The most commonly used race scheme identified 16 races of SCN. The race designation allowed nematologists and soybean breeders to share information about the ability of certain SCN populations to reproduce on soybean varieties that contain certain genes for resistance to SCN.

In 2003 the HG Type Test was adopted to replace the race test. This new test includes seven sources of resistance (germplasm lines) and the results are shown as a percentage, indicating how much the nematode population from a soil sample increased on each of the seven lines. This test indicates which sources of resistance would be good for the field being tested and which would be poor. Since the genetic sources of resistance are limited in commercially available soybean varieties, it is important to rotate these "sources of resistance" to delay the build up of a virulent SCN population.

Not all varieties with the same source of resistance have comparable yields, nor do they respond identically to SCN. Consult Soybean Variety Trial data for SCN-resistant soybeans that are adapted to your region.

SCN egg distribution

A soil analysis is the only way to determine whether SCN is present at detectable levels in a field. It is estimated that even when 2 million eggs are present per acre of soil, there is only a 63 percent chance of detecting one egg if one pint of soil is examined. Distribution of SCN in a field is neither random nor uniform. Numbers of SCN and extent of SCN-related plant damage will depend on soil type, soil temperature, soil moisture, overwinter survival of SCN, soil nutrient level, crop host status (host or nonhost), and the presence of other plant pathogens or natural enemies of SCN. A good soil sampling pattern will ensure that a reliable average of the SCN population is obtained. One cannot determine areas in fields at high risk of yield loss to SCN if soil samples are not representative of the field.

Sampling fields for SCN

Once a field is known to be infested with SCN, soil samples need not be collected each year. Soil samples from these fields should be collected before SCN-susceptible varieties are grown again or once every three years if resistant varieties are grown in a rotation.

Although soil samples for SCN may be collected at any time, the ideal time to sample is as close to soybean harvest as possible. SCN numbers tend to be highest when the plants are almost mature to shortly after harvest. Sampling near harvest allows sufficient time for the nematode laboratory to process the sample and provide you with information, and enough time for variety selection or choosing alternative crops for the next year.

Large fields may be subdivided into sections of about 10 acres each and a single sample from each of the different sections submitted for analysis. Collect 10 to 20 soil cores six to eight inches deep in a zigzag pattern across the area to be sampled. Bulk the cores in a bucket and mix thoroughly. Place about one pint of mixed soil in a plastic bag and label the outside of the bag with a marker to identify the field number and owner. Store the sample away from sunlight in a cool area until it is shipped to the laboratory.

Testing for SCN

Check SCN Diagnostics to see what tests are available.

Send your soil samples to

- SCN Diagnostics

1721 East Campus Loop

Columbia, MO 65211-5315

Phone: 573-884-9118

Managing soybean cyst nematode

Uninfested fields

- Avoid introducing SCN whenever possible

SCN can be spread on anything that moves soil. It is not possible to eradicate SCN from a field once it has become established. Work uninfested fields first to avoid spreading SCN in soil.

Infested fields

- Rotation

Rotate soybeans with crops that are not SCN hosts. SCN cannot reproduce if host plants are not present. Rotate sources of genetic resistance in soybean varieties if possible. A certain percentage of SCN individuals can reproduce on resistant varieties. If sources of resistance are not rotated, these individuals can produce a SCN race shift. This will reduce the effectiveness of genetic resistance available in commercial soybean varieties. - Maintaining plant health

Plant stress from drought, nutrient deficiencies, weed infestation, insects, and other plant diseases will aggravate plant damage caused by SCN. - Resistance vs. nematicides

Resistant germplasm is more reliable and cost-effective than nematicides in reducing SCN populations. - Weed control

Reduce weeds in fields, because weeds can also be SCN hosts.