Double-cropping soybeans after winter wheat has grown in popularity and feasibility in much of Missouri. This cropping system has several advantages. A crop, growing on the land all year, provides control of soil erosion. Spreading annual fixed costs such as land, taxes and machinery over two crops instead of one may increase gross returns per acre with relatively low increases in production costs. Thus profits per acre may be increased.

A successful wheat-soybean double crop depends on management and weather conditions. Establishing an adequate soybean stand and effective weed control are critical. In northern Missouri, there are few days left in the season after wheat harvest for planting soybeans, and that's a constraint. So knowing the conditions to which double cropping is best adapted will provide for a successful second crop. It will also permit farmers to avoid high-risk years.

Double-crop wheat management

A successful double-crop system begins with proper management of winter wheat. A good, fully tillered and adequately fertilized wheat stand usually suppresses weeds until harvest. The smaller the weeds in the wheat, the more easily they can be controlled in the soybeans. Where weeds are a problem in wheat, several herbicides are available to control broad-leaved weeds and grasses. In selecting a herbicide, consider the type of weed problem and the potential residual effect of the chemical on the soybeans.

Variety

An ideal wheat variety in a double-crop system consistently produces high yields of high-quality grain, yet matures early enough to permit timely establishment of soybeans. In Missouri, high yield and quality are usually associated with good winter hardiness and early maturity. However, avoid very early flowering varieties because of the danger of frost damage in the spring. When selecting a variety for high yield, consider performance results from several locations and years.

Fertilization

Fertilizing for both crops at once is more practical than trying to make an additional application after wheat harvest. Time will be saved at a critical period. Also, if the soybeans will not be tilled, the fertilizer will already be in the soil. The higher fertility level may also benefit the wheat. If the soybean double crop cannot be planted, the extra phosphorus and potassium applied will remain in the soil to benefit subsequent crops.

Base the amount of fertilizer to be supplied on the soil fertility status and the crop yield expectations of both crops. Determine the soil fertility status with a reliable soil test, and base expected crop yield on past experience. Most Missouri soils require the application of both phosphorus and potassium to provide for the two crops in this system (Table 1).

Table 1. Fertilizer application rates for double-crop wheat-soybeans as determined by crop yield and soil test values.

| Double crop yield per acre | Pounds fertilizer recommended per acre | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphorus soil test level1 | Potassium soil test level2 | ||||||

| Wheat | Soybeans | Low | Medium | High | Low | Medium | High |

| 40 bushels | 20 bushels | 90 | 60 | 20 | 85 | 50 | 20 |

| 30 bushels | 100 | 65 | 20 | 95 | 70 | 25 | |

| 40 bushels | 105 | 75 | 20 | 110 | 80 | 40 | |

| 60 bushels | 20 bushels | 100 | 70 | 20 | 90 | 55 | 25 |

| 30 bushels | 110 | 80 | 20 | 105 | 75 | 30 | |

| 40 bushels | 120 | 85 | 25 | 120 | 85 | 45 | |

| 80 bushels | 20 bushels | 115 | 80 | 20 | 95 | 60 | 25 |

| 30 bushels | 120 | 90 | 25 | 110 | 80 | 35 | |

| 40 bushels | 130 | 100 | 30 | 125 | 90 | 45 | |

| 1. Low, medium, and high Bray I phosphorus soil test levels are 10, 30 and 60 pounds phosphorus per acre, respectively. 2. Low, medium, and high potassium soil test levels are 150, 250 and 350 pounds potassium per acre, respectively, for a soil with a cation exchange capacity (CEC) of 12. | |||||||

Planting date

Wheat is a cool-season crop that grows at temperatures as low as 37 degrees Fahrenheit, although best growth is between 70 and 77 degrees Fahrenheit. It can be planted from early September to mid-November. But it is preferable to plant it in late September or early October in northern Missouri and by mid-October in southern Missouri.

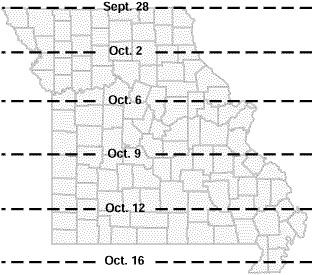

If a variety is susceptible to the Hessian fly, delay planting until after the fly-free date. The fly-free date ranges from Sept. 28 at the Iowa line to Oct. 17 at the Arkansas line (Figure 1).

The best wheat yields often result from plantings made just after the fly-free date. Very early planting subjects the wheat to attack by insects and certain diseases. Late planting results in less tillering, more chance of winter injury and a lower yield. To compensate for the reduced tillering associated with late planting, increase the seeding rate. The planting date has little effect on when wheat matures unless emergence is delayed until spring.

Seeding rates

For wheat planted at the recommended time, a seeding rate of 1-1/2 is normally adequate. This amount may be adjusted up or down depending on the date of seeding and on seed size. If seed is excessively large, more will be needed to obtain the same plant population. Because wheat tillers well under favorable environmental conditions, higher than recommended seeding rates seldom result in yield increases, unless planting is delayed until late in the fall.

Wheat is most often planted into a prepared seedbed, although no-till is becoming more popular. Drilling into rows gives higher yields than broadcasting followed by incorporation. Tillage practices that leave some plant residue on the surface help retard erosion and reduce surface crusting, although these practices may increase insect and disease survival. Use a no-till system if you can achieve good weed control and seed placement in the soil. With no-till, you must uniformly plant the proper number of seeds about 1 inch deep and cover them well.

Harvest

The yield of full-season soybean varieties decreases slightly more than 1 bushel per week as planting is delayed from early to late June. In July, yields decrease 3 to 5 bushels per week. Decreases are greater in the north than in the south. Thus, it is important to harvest the wheat and plant the soybeans as early as possible, especially in northern areas.

If you have grain drying facilities, consider harvesting the wheat at 19 to 22 percent moisture and drying it. Besides permitting earlier planting of the double crop, early harvest results in less field loss from shattering and lodging. Do not dry wheat at temperatures above 110 degrees Fahrenheit if it is to be used for seed or above 140 degrees Fahrenheit if it is to be milled.

Windrowing wheat is another alternative that permits early soybean planting. Wheat can be windrowed at moisture up to 40 percent. In general, drying occurs more rapidly with windrowed wheat than standing wheat. Some homemade attachments move the windrows to allow planting immediately after cutting. However, unless they have other uses on the farm, a windrower and pick-up attachment for the combine may be too costly to be offset by gains due to earlier planting.

Straw management

Wheat straw can act as a surface mulch to conserve moisture, impede runoff and prevent surface crusting. No-till practices are valuable in situations where moisture for germination is limited, as is normally the case at wheat harvest, and especially when planting is delayed after the wheat has been removed from the field. However, residues can complicate planting and interfere with herbicides. These problems can be overcome with proper equipment and straw management.

In a no-till system, small grain residue should not be bunched or windrowed unless it is to be baled and removed. Planters cannot penetrate such residue and still place seed at the proper depth. A simple way to manage wheat straw in a no-till system is to cut the wheat at normal height, shred the straw with a shredder attachment on the combine, and distribute it evenly on the field. If this cannot be done, then one or two passes with a rotary chopper, set at 6 to 12 inches high, will shred and spread the straw.

Shade provided by standing stubble stimulates elongation of soybean stems and causes a higher first pod height. This makes soybean harvest easier and reduces harvest losses. If the stubble is too high, plants will be spindly and susceptible to lodging.

With no-till systems, burning the wheat straw to eliminate residue seldom produces yields greater than those achieved by chopping and spreading the straw.

Double-crop soybean management

In many years, the final decision to double crop soybeans should be made only after wheat harvest. Ask these questions: Is there enough moisture to germinate the soybeans? Is there enough of the season left for a reasonable crop to mature before first frost? Can other problems such as weeds be controlled? Avoiding problems greatly improves the long-term profitability of double cropping.

The planting decision

In double cropping, rapid germination and emergence of a uniform stand of soybeans are keys to success. Soil moisture is the critical environmental factor determining whether a good stand is obtained. If the soil is too dry for prompt emergence, many seeds may die, or emergence may be so late that the remaining season is too short for the crop to complete growth. If the top 2 inches of soil are dry, and if soybeans will not germinate and emerge without more water, wait. If rainfall is not sufficient for stand establishment by the latest safe date to plant, abandon double cropping for that year. The low probability of rainfall during late June and July (Table 2) precludes double-crop soybeans in some years, particularly in central and northern Missouri.

Table 2. Probability of rainfall during one-week periods in June and July in Missouri.

| Location | Rainfall (inches) | Percent probability for the week ending | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| June | July | August | ||||||||

| 7 | 14 | 21 | 28 | 5 | 12 | 19 | 26 | 2 | ||

| Clinton | 0.6 | 78.2 | 58.4 | 57.5 | 40.8 | 45.2 | 35.7 | 39.9 | 36.5 | 46.0 |

| 1.0 | 64.0 | 44.4 | 46.3 | 27.0 | 31.6 | 24.8 | 27.0 | 20.4 | 30.1 | |

| 1.2 | 56.1 | 38.1 | 41.5 | 22.1 | 26.5 | 20.7 | 22.0 | 15.1 | 24.3 | |

| Columbia | 0.6 | 55.2 | 48.8 | 57.7 | 44.5 | 38.4 | 37.8 | 39.6 | 37.1 | 54.2 |

| 1.0 | 38.8 | 35.5 | 41.7 | 30.9 | 25.8 | 24.1 | 24.7 | 23.2 | 37.5 | |

| 1.2 | 32.5 | 30.4 | 35.2 | 25.8 | 21.3 | 19.3 | 19.6 | 18.5 | 31.1 | |

| Hannibal | 0.6 | 59.0 | 52.1 | 48.1 | 38.9 | 36.9 | 35.9 | 36.2 | 36.7 | 47.5 |

| 1.0 | 40.4 | 39.2 | 33.3 | 20.0 | 23.7 | 24.1 | 25.6 | 23.9 | 32.8 | |

| 1.2 | 33.3 | 34.2 | 27.9 | 14.2 | 19.0 | 20.0 | 21.7 | 19.5 | 27.4 | |

| Kirksville | 0.6 | 63.4 | 58.3 | 47.5 | 51.3 | 35.7 | 41.2 | 44.7 | 36.1 | 54.7 |

| 1.0 | 46.2 | 45.8 | 34.5 | 35.3 | 23.1 | 28.7 | 35.0 | 22.8 | 39.2 | |

| 1.2 | 39.2 | 40.8 | 29.7 | 29.3 | 18.7 | 24.0 | 31.1 | 18.3 | 32.9 | |

| Poplar Bluff | 0.6 | 53.8 | 46.7 | 48.5 | 47.6 | 32.0 | 36.0 | 42.4 | 40.2 | 37.3 |

| 1.0 | 41.8 | 33.0 | 30.1 | 36.5 | 18.6 | 23.1 | 24.5 | 27.3 | 25.8 | |

| 1.2 | 36.8 | 27.7 | 23.3 | 32.0 | 14.3 | 18.6 | 18.3 | 22.6 | 21.6 | |

| St. Louis | 0.6 | 53.6 | 46.6 | 43.6 | 36.6 | 36.5 | 33.8 | 36.4 | 33.4 | 46.0 |

| 1.0 | 37.1 | 31.5 | 26.6 | 22.7 | 25.8 | 21.3 | 23.8 | 19.9 | 31.5 | |

| 1.2 | 30.8 | 26.0 | 20.8 | 18.0 | 21.9 | 17.1 | 19.4 | 15.3 | 26.2 | |

| Springfield | 0.6 | 58.6 | 52.5 | 53.5 | 49.7 | 41.1 | 40.5 | 39.0 | 32.1 | 44.2 |

| 1.0 | 42.1 | 40.9 | 39.6 | 34.1 | 28.4 | 27.0 | 26.9 | 19.9 | 30.6 | |

| 1.2 | 35.4 | 36.3 | 34.1 | 28.1 | 23.7 | 22.1 | 22.5 | 15.8 | 25.7 | |

| Trenton | 0.6 | 61.2 | 60.5 | 57.9 | 57.8 | 45.8 | 42.1 | 21.4 | 45.2 | 50.3 |

| 1.0 | 46.6 | 46.2 | 42.9 | 42.0 | 31.6 | 31.0 | 9.9 | 30.0 | 36.1 | |

| 1.2 | 40.8 | 40.2 | 37.0 | 35.7 | 26.4 | 26.8 | 6.8 | 24.5 | 30.7 | |

The need to conserve moisture through practices such as no-till is obvious. More important, however, is that following these practices eliminates the major source of failures in double cropping before most variable costs associated with soybeans are incurred.

If adequate moisture is available immediately below the 2-inch depth, an alternative is to use furrow openers or similar devices to move the dry topsoil. Plant into the moist soil. However, do not plant deep to moisture without moving the dry topsoil.

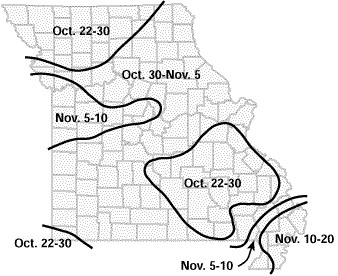

The last safe date to plant soybeans is determined by the amount of remaining growing season at a location. At least 90 frost-free days are needed for double-crop soybeans to reach physiological maturity. Subtracting 90 days from the average date of the first killing frost in the fall gives the last average safe date for emergence of double-crop soybeans (Figure 2).

Freezing affects a crop differently depending on its growth stage. When freezing occurs before physiological maturity, yield and quality are reduced. Physiological maturity coincides with maximum dry weight accumulation in the seeds and occurs when seed moisture is still 50 to 60 percent. A visible indicator is yellowing of the pod walls. After the beans have reached physiological maturity, moderate freezing does not affect yield or industrial quality.

There is ample growing season in southeast Missouri for double cropping because of the relatively early wheat harvest (by June 20 to 25, 75 percent is harvested) and the late fall frosts. But farther north, the interval between wheat harvest and fall frost narrows to just over 100 days. So while double cropping soybeans after wheat should be possible in much of Missouri, it is more difficult in the north.

Choosing a variety

Desirable soybean varieties for double cropping use as much of the season as possible, yet they mature soon enough to avoid losses due to frost. Generally, they are medium-season varieties for the normal planting time in an area. These varieties should produce adequate vegetative growth to form the closed canopy needed to shade out weeds.

Varieties maturing too early are short, have pods closer to the soil surface, are more difficult to harvest, and are lower yielding. Late varieties may have favorable growth, but will still be green at the time of the first killing freeze. Because of their low height and short flowering period, determinate semidwarf varieties should not be used for double cropping.

Research data have shown that when double cropping wheat-soybeans, a late Maturity Group 2 variety is well adapted to northern Missouri, a late Maturity Group 3 to the central part of the state, and a Maturity Group 4 to southwest Missouri. Varieties of maturity Maturity Group 5 can be grown in the Delta Region.

After reaching maturity, soybeans require about two weeks of field drying time. For example, in northern Missouri, wheat should be seeded by the end of October. But double-crop beans are not likely to be harvested by that date. So wheat planted after harvest of double-crop soybeans would not gain sufficient winter hardiness. Therefore, in central and northern Missouri the full-season soybean-wheat double crop sequence can be followed every second year.

An alternative is to overseed wheat from an airplane or a high-clearance implement just before soybean leaf-drop. Then the falling leaves form a mulch over the seeds. Except on light soils that dry out quickly, good wheat establishment has been obtained with this practice.

Row width

When soybeans are planted late in the normal growing season, there is less time for vegetative growth to take place. Less branching occurs in double-crop beans; therefore, canopy development seldom fills the space between wide rows. Research in Missouri shows that drilled or narrow rows (less than 20 inches) can result in a 15 to 20 percent increase in yield over wider rows.

Doubling back with a row planter to split 30-inch middles is a useful way to get narrow rows. In a no-till system, being a little off center doesn't make much difference because there is no cultivation.

Seeding rates

In full-season soybeans, plant population can vary widely without affecting yield. However, in double cropped soybeans, an above-average plant population may increase yield. Also, higher seeding rates are recommended (Table 3) where soybeans are planted in no-till fields and there is difficulty in controlling depth or getting good slot closure. A rate of seven to eight seeds per foot is suggested for 20-inch rows. This normally requires 80 to 100 pounds of seed per acre. Table 3 shows that as row width decreases, the number of plants per foot of row should also decrease for better plant distribution.

Table 3. Suggested plant populations and seeding rates for no-till, double-crop soybeans planted at various row widths.

| Row width | Final stand desired | Seeding rate required per acre 1 |

|---|---|---|

| 30 inches2 | 9 to 10 plants per foot | 85 pounds |

| 20 inches | 7 to 8 plants per foot | 100 pounds |

| 15 inches | 5 to 6 plants per foot | 100 pounds |

| 7 to 10 inches | 3 to 4 plants per foot | 135 pounds |

| 1. Assumes 60 percent emergence rate and approximately 3,200 seeds per pound. 2. Avoid if possible. | ||

Pest control

Most often in no-till, double-crop soybean production, herbicides are required to control existing weeds and those emerging later. Herbicides such as paraquat or Roundup can be used to control existing vegetation after wheat harvest. Paraquat can be used on small annual weeds. Roundup can be used on most small weeds but would be preferable to paraquat on large or perennial weeds. It is sometimes difficult getting herbicides to penetrate through heavy straw residue to the small weeds underneath. It may be useful to mount a spray bar under the combine to spray this small vegetation before spreading the straw.

Grass and broadleaf herbicides are often needed to control weeds that emerge after planting. Appropriate herbicides can be selected for either preemergence or postemergence application. Heavy straw cover may reduce the amount of preemergence chemical that reaches the soil surface, although a rain after planting often washes enough of the chemical off the straw to provide effective weed control. Using the high end of the range of recommended application rates may result in more herbicide reaching the soil surface. When using the no-till system, most preemergence products can be applied with the herbicide used to control weeds existing at the time of planting.

A broad range of postemergence herbicide options now exist, including several that, when used with appropriate soybean varieties, control most species of weeds. A major advantage of postemergence chemicals is that they are applied after one has had a chance to assess the soybean stand and the types and numbers of weeds present. If the stand is poor or if only certain weeds are a problem, then money won't be spent on unnecessary herbicides. Problems associated with relying entirely on postemergence chemicals include competition of weeds for moisture until they are suppressed or killed and the inability to control weeds if they are too large at the time of treatment.

First, determine your weed problems and existing conditions, then read herbicide labels for the proper use and application recommendations.

Double-crop soybeans often escape pests that cause problems in full-season beans. However, severe pest damage can be more serious to double-crop beans because plant foliage is minimal and all available leaf area is needed for good production. So what may be minor damage on large, full-season beans may be serious damage on double-crop beans, requiring treatment earlier. Be aware that because expected double-crop yields are lower, serious consideration should be given to potential productivity and the economics of the double-crop beans before initiating expensive treatments.