As much as 80 percent of the water used around the home during summer is used outside. Watering the lawn is the main outside water use. During dry summers, local water authorities may cut off water for outside use or only allow watering on certain days. Both measures are necessary and effective means of reducing water use and relieving the strain on city water supplies.

To avoid severe loss of turfgrass and to conserve water, homeowners should manage their lawns each year in anticipation of water restrictions.

This guide describes that will reduce the need for irrigation while improving the competitiveness and appearance of your lawn.

Learn to read a lawn and know when to water

Turfgrass water-use rates are high during sunny and windy days with low relative humidity. In situations where lawns are not watered and rainfall is limited, grasses first show symptoms of wilt and later turn completely brown.

Signs that a lawn should be thoroughly watered for grasses to remain green and actively growing

- Grass blades turn bluish-purple, indicating plant wilt.

- Footprints remain in the lawn for several hours. Leaves with plenty of water quickly return to their rigid upright shape, but leaves lacking water will remain trampled for a period of time.

- Leaves are folded or rolled lengthwise along the blade.

- If high temperatures and dry conditions continue without rain or irrigation, the aboveground portion of grasses will turn entirely brown. Grasses are said to be dormant during this browned-out stage because the lower portion of the plant called the crown, usually remains alive but is not growing. Thorough watering will bring the lawn out of dormancy, and new growth will resume from the crown of the grass plants.

- Although grasses are dormant, watering restrictions that result in extended dry periods can cause large ground cracks, severe soil-drying and excessive loss of turfgrass cover even when watering is resumed later in the summer or early fall.

- Summer dormancy of grasses is a mechanism that helps a lawn survive, but it does not guarantee that a lawn will fully recover from the browned-out stage.

- Dormant lawns should receive at least 1 inch of water every two or three weeks during summer to prevent complete turfgrass loss. Grasses may not show a noticeable greening but that amount of irrigation should be sufficient to hydrate the lower plant portions and increase the recovery once adequate moisture is available.

- Wet wilt is another type of wilt to look for. Wet wilt occurs when the soil is obviously wet, but the root system is not able to keep pace with the water demands from the atmosphere. The curling of leaves from wet wilt looks very similar to wilt caused by lack of soil moisture. Waterlogged lawns that have a shallow root system are susceptible to wet wilt on hot days when plant transpiration rates are higher. Do not add more water when lawns are wilting and soil moisture appears to be adequate, for it will only aggravate the problem by starving the root zone of oxygen.

Prepare for a drought

Management practices in the fall and spring determine the drought tolerance of the lawn in summer. To reduce the need for irrigation, your lawn management program should maximize root volume and depth in preparation for summer drought. By the time summer arrives, you can do little to help a lawn except mow and irrigate properly.

The following lawn-care tips will help reduce the need for irrigation and increase the chance of surviving summer drought.

- Avoid the temptation to irrigate in spring just to get grass growing. Allow it to green up naturally. Mow frequently and avoid scalping. Do not begin to irrigate until dry conditions of early summer cause obvious turfgrass wilt that lasts for more than one day.

- In the spring, atmospheric water demands are low, and moderate wilting of turfgrass does not damage the lawn.

- If the soil is allowed to dry slightly in the spring and the grass to wilt some, a deeper and more-hardy root system will develop. Such a root system will be necessary to reduce the need for summer irrigation and to survive drought conditions or city water restrictions.

- Mow grass as tall and as frequently as possible with a properly sharpened blade to produce a dense cover with a deep root system. Taller grasses develop a deeper root system that draws moisture from a larger volume of soil and results in less need for irrigation.

- Grass height should never be less than 2-1/2 inches after mowing. Mow frequently enough so that clippings are only one-third the total height of the grass plant. A lawn mowed at heights of 3 to 3-1/2 inches will have a better chance of surviving prolonged drought and water restrictions. Most homeowners mow lawns once a week regardless of the mowing height. But taller mowing heights are less likely to cause turfgrass scalping, especially when grass leaves are rapidly growing in the spring. Dull mower blades and scalped turfgrass result in an unattractive lawn that too many homeowners try to correct with overwatering.

- Apply nitrogen fertilizer to cool-season grasses (Kentucky bluegrass, tall fescue and perennial ryegrass) primarily in the fall.

- Some nitrogen may be applied in the spring if the lawn is sparse and bare soil is visible. Avoid summer application of nitrogen. Nitrogen fertilizer applied in the spring and summer causes excessive leaf growth, which uses stored plant energy that normally would be used to produce roots needed for water uptake during summer.

- Test the soil to ensure an adequate amount of phosphorus and potassium. Additional applications of potassium — one pound of K2O per 1,000 square feet — in April and again in May or June will improve summer lawn performance.

- Core aerify cool-season lawns in the fall or spring to increase air, water and nutrient movement into the soil. This builds better root systems. Avoid summer coring in the absence of water because it may cause excessive drying and drought stress.

- Limit thatch removal by power raking or verticutting to early spring or fall, when water demands are low and turfgrass recovery is rapid. Do not severely power rake lawns in the late spring or summer or they will require excessive irrigation to remain alive. When necessary, severe power raking and seeding should be done in September on cool-season lawns..

- Select grasses that require less summertime irrigation to remain attractive. Zoysia is a warm-season grass more tolerant to heat and drought, and tall fescue is a more deeply rooted cool-season grass. Both are noted for their ability to make an attractive summer lawn with less irrigation.

Select a sprinkler that best fits your needs

Automatic irrigation systems with pop-up sprinklers are often associated with excessive irrigation. However, properly designed and operated systems supply water uniformly over an entire area without wasted runoff.

Missouri soils generally have low water-infiltration rates. Automatic controllers can be set to supply several short cycles so that the total amount of water desired is supplied without runoff.

The most common type of watering occurs with hose-end sprinklers. Some studies have shown that the average homeowner applies 2-1/2 times the amount of water required for overgrowth when using hose-end sprinklers.

Several types of hose-end sprinklers are available (Figure 1). Select one that best fits the size and shape of your lawn, and operate it efficiently. All hose-end sprinklers can be attached to inexpensive timers that can be used to shut off unattended sprinklers and avoid overwatering.

Figure 1

Some sprinkler types and their applications

| Sprinkler types | Comments |

|---|---|

Rotary or pulse |

Rotary head shoots water out in a pulsating action. Some have adjustable screw or paddle that breaks up jet stream and disperses water pattern. Can be set to water partial circles. Best for large areas. Accurately distributes water when placed in an overlapping triangular pattern. |

Traveling |

Path guided by hose placement. Traveling action covers a large area without assistance. Requires level ground and overlapping pattern to evenly distribute water. Used primarily on large lawns. Can easily be manipulated for large irregular, lawn shapes. Wheel drive types are not suitable for newly seeded lawns where soft soil conditions result in stuck sprinklers. |

Whirling-head |

Deposits largest amount of water closest to spray head. Use a 50 percent overlapping pattern. Deposits larger amount of water in short period of time and requires frequent movement. Good for watering tight locations. |

Stationary |

Applies water in irregular pattern even with overlapping moves. Difficult to water large areas uniformly. Good for spot-watering tight locations. Deposits a large amount of water in a short period of time and requires frequent movement. |

Oscillating |

Delivers water in a rectangular pattern. Deposits most of the water near sprinkler head. Difficult to achieve even water pattern on large areas that require sprinkler relocation. Can be adjusted to water smaller rectangular areas and other tight locations. |

Soaker-hose |

Flat pin-holed hose sprays fine streams of water. Requires several moves to water medium-sized lawn. Delivers water slowly — good for hard-to-wet locations. Can be manipulated to water irregular areas and long tight areas along house or walks. |

How much water to apply

Once you have selected the best sprinkler for the size and shape of your lawn, you must decide how long to operate a sprinkler in a certain location. To make an informed decision, you need to know how many inches of water your system puts out in a certain amount of time. Take the following steps to determine your system’s water application rate:

- Place shallow, straight-sided containers (tuna cans work well) or rain gauges in a grid pattern around the sprinkler.

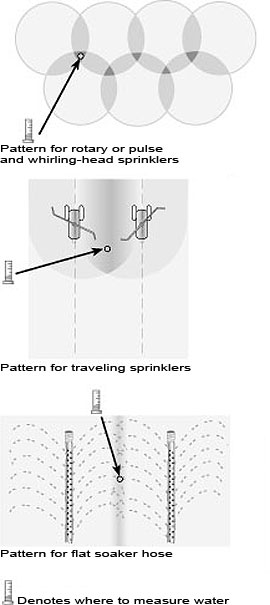

- Operate the sprinkler, using overlapping patterns (Figure 2) where needed, for a given amount of time.

- Measure the depth of water in the cans with a ruler or read directly from the rain gauges.

- Use the calculation in Example 1 to determine your water application rate in inches per hour.

Figure 2

Proper sprinkler pattern overlap of 50 percent.

Example 1

If a sprinkler delivers 1/4 inch of water in 45 minutes, then how much water does it apply in 1 hour (60 minutes)?

0.25 inch ÷ 45 minutes = X inches ÷ 60 minutes

(0.25 inch x 60 minutes) ÷ 45 minutes = 0.33 inch per hour

An alternative approach would be to measure the area that your sprinkler pattern covers and the length of time it takes to fill a one-gallon container directly from the sprinkler. Example 2 describes how to calculate your water application rate using this approach.

Example 2

If a sprinkler takes 1 minute and 13 seconds (73 seconds) to discharge 1 gallon of water, then how many gallons of water can it discharge in 1 hour (3,600 seconds)?

1 gallon ÷ 73 seconds = X gallons ÷ 3,600 seconds

(1 gallon x 3,600 seconds) ÷ 73 seconds = 49 gallons in 1 hour

If 49 gallons of water is applied to 235 square feet per hour, then how many gallons are applied to 1,000 square feet in 1 hour?

49 gallon ÷ 235 square feet = X gallons ÷ 1,000 square feet

(49 gallons x 1,000 square feet) ÷ 235 square feet = 208 gallons per 1,000 square feet

If 624 gallons of water equals 1 inch of water per 1,000 square feet, then how many inches of water will 208 gallons of water provide per 1,000 square feet?

(1 inch per 1,000 square feet) ÷ 624 gallons = (X inches per 1,000 square feet) ÷ 208 gallons

(1 inch x 208 gallons) ÷ 624 gallons = 0.33 inches per 1,000 square feet

In the above examples, sprinklers should be operated about three hours in each location to supply 1 inch of irrigation water per week.

Most soils in Missouri will absorb only about 1/2 inch of water per hour. If your sprinkler system delivers more than 1/2 inch of water per hour, move it to a different location more frequently, after each time 1/2 inch of water has been applied. Repeat the process until the full amount of water desired has been applied.

Rotary sprinklers that are set to deliver a half or quarter sprinkler pattern will discharge two or four times the amount of water on a given area, respectively. Operate rotary sprinklers with half patterns for half the amount of time and sprinklers with quarter patterns for one-quarter the amount of time.

The utility water meter connected to your home can also be used to check how effectively water is being applied. It accurately measures water in cubic feet. When no other water is being used in the home, water a known area for a set amount of time, and use these conversion factors to determine your water application rate:

- 624 gallons (83.3 cubic feet) of water are required to apply 1 inch of water on 1,000 square feet of lawn.

- 7.48 gallons = one cubic foot of water.

Once you have decided that your lawn has sufficiently wilted and irrigation is needed, supply enough water to last a week. Depending on the type of sprinkler and the soil water infiltration rate, several sprinkler changes may be required over a two- or three-day period to supply the amount of water desired.

If no rainfall occurs, continue to irrigate on a weekly schedule. If rainfall does occur, delay the next irrigation until symptoms of wilt are present. Even though water application is discussed on a weekly basis, it is not crucial that water be applied every seven days. Keep the application schedule flexible, and irrigate based on the determination of lawn wilting and soil moisture.

Table 1

Approximate lawn water requirements

| Lawn type | Green Turf1 | Dormant Turf2 |

|---|---|---|

| Perennial ryegrass | 1.5 inches of water per week | 1.0 inches of water per week |

| Kentucky bluegrass | 1.2 inches of water per week | 0.7 inches of water per week |

| Tall fescue | 0.8 inches of water per week | 0.5 inches of water per week |

| Zoysia or bermuda | 0.5 inches of water per week | 0.2 inches of water per week |

| Buffalograss | 0.3 inches of water per week | 0.2 inches of water per week |

1Lawn remains green and growing

2Lawn may turn brown, but will not die

Once you have decided to irrigate, use Table 1 to determine the appropriate amount of irrigation for your lawn and develop an irrigation schedule. Should puddles or runoff occur before the total amount of water is applied, stop irrigating and resume only after the ground has absorbed the free moisture. Lawn areas that are moist, firm and have no visible water are ready for a repeat irrigation cycle. Areas that are soft and produce squashy footprints when walked on are not ready to receive additional irrigation.

One day after watering, check a few different locations in the yard to determine how well your irrigation program is distributing water in the root zone. With a shovel, cut a slender 2-inch wedge 6 to 8 inches deep. This wedge of soil, roots and turfgrass can be replaced easily without damage to the lawn after inspection.

Estimate the moisture content at different depths in the soil profile by pressing together a golf ball–sized amount of soil. If drops of water can be squeezed from the soil ball, you may be irrigating too much or too often. Soils that hold together without crumbling and appear moist have been irrigated properly. Soils that appear dry and dusty and do not form a ball when squeezed have not received enough irrigation or the water is running off the surface of the lawn and not into the root zone.

Adequate soil moisture 6 to 8 inches deep is sufficient to maintain grasses during the summer. A foot-long slender screwdriver pushed into the ground in several locations can also give a quick assessment of the moisture condition of the soil. The screwdriver will easily penetrate to the soil depth that has received sufficient water. The screwdriver test can also be used to help determine where and when irrigation is needed.

Conserve water by knowing when to water

From an agronomic standpoint, the best time to water a lawn is from 6 to 8 a.m. During this time, disruption of the water pattern from wind is low, and water lost to the atmosphere by evaporation is negligible. Watering early in the morning also has the advantage of reducing the chance of turfgrass diseases that require extended periods of leaf moisture. Avoid irrigation during midday and windy conditions. For any local irrigation guidelines, follow the ordinances established by your local municipal or county.

Move sprinklers frequently enough to avoid puddles and runoff. Difficult-to-wet areas such as slopes, thatched turfgrass and hard soils may benefit from application of a wetting agent to improve surface penetration of water.

Water only when the plant tells you to. Become familiar with areas of the lawn that wilt first — bluish-purple leaves, rolled leaves, foot printing. Water within a day of observing these symptoms.

Water problem areas by hand to postpone the need for irrigation of the entire lawn. Some areas of a lawn usually wilt before others. These areas, called “hot spots,” may be caused by hard soils that take up water slowly, slopes, southern exposures and warmer areas next to drives and walks. Lawns that have unusual shapes also may require some hand-watering to avoid unnecessary watering of paved surfaces, mulched beds and buildings. Soaker hoses that have a narrow pattern and supply water at a slow rate may be useful in these areas.

Watering new lawns

Newly seeded or sodded lawns require special irrigation. A newly seeded lawn should be watered daily and may need as many as four light waterings in a single day. Keep the seedbed moist, but not saturated, to a depth of 1 to 2 inches until germination occurs (green cast to lawn and seedlings are 1/4 to 1/2 inch tall).

Seedlings of a new lawn must not be stressed to the point of wilt. Continue with light applications of water — 1/8 to ¼ inch — one to four times a day.

Apply straw (one bail per 1,000 square feet) at time of seeding to help shade the ground and prevent rapid drying of the soil surface. Straw also will reduce seedling damage from the force of large sprinkler drops. Watering with a light mist is best for establishing new lawns. As seedlings reach 2 inches in height, gradually reduce the frequency of watering and water more deeply. After the new lawn has been mowed two or three times, deep, infrequent waterings are the best.

Newly sodded lawns require watering one or two times a day. Begin irrigation immediately after laying sod. Plan your sodding operation so that a section of laid sod can be watered immediately while other areas are being sodded.

Sod should be watered so that both the sod strip and the top inch of soil below the sod are wet. The first irrigation will take about an inch of water to completely wet the sod. After watering, lift up pieces of sod at several locations to determine if it has been adequately irrigated. Continue watering one to two times a day with light irrigations to prevent wilting and to ensure moist soil just below the sod layer.

As sod becomes established and roots penetrate and grow in the soil, gradually reduce the frequency of watering. After sod has been mowed two or three times, irrigate deeply and infrequently. During hot, windy conditions, establishing sod may require several light mistings per day to prevent wilt and potentially lethally high temperatures. In this case, light misting, just to wet the leaf surface and not to supply water to the soil, cools the grass plant as water is evaporated from the leaves.

Do not overwater, or saturate, the soil because that will inhibit sod roots from growing into the soil. If the sod cannot be watered on a daily basis, thoroughly water the sod and soil to a depth of 6 inches. Although this will delay the rooting time of sod, it will also reduce the chance of rapid drying and severe loss of grass.

Summary

Good lawn care practices save water and harden turfgrass in preparation for dry periods or local lawn-watering restrictions. Taller mowing and fall nitrogen fertilization fertilization of cool-season grasses develop a hardy and efficient root system that reduces the need for supplemental irrigation.

Irrigation schedules should be kept flexible and associated with identification of lawn wilting. Choose a sprinkler that best fits the size and shape of your lawn. Determine the amount of water the sprinkler applies to accurately water your lawn. During establishment of newly seeded or sodded lawns, water daily. After a new lawn has been mowed a few times, water deeply and infrequently.