For a beginning beekeeper, between two and five hives is ideal. This size apiary is small enough for a beginner to manage but still provides enough bees to allow for winter losses. Expand in a couple of years, after you have gained experience and confidence. Once a hive has become established, it can produce 50 to 100 pounds of surplus honey each year.

Take a beginning beekeeping class before you invest in bees and equipment. Between varroa mites and colony collapse disorder, knowledge of beekeeping management practices is essential. Check with your local MU Extension center about upcoming classes.

Join local and state beekeeping associations for additional information and guidance. Attend any seminars or meetings that are offered to expand your education and to meet other beekeepers, who can provide valuable help. For additional information, check out some of the many good reference books on apiculture.

When you are ready to buy supplies, you will have many beekeeping supply companies to choose from; a few are listed near the end of this guide. You can buy prebuilt hive kits that include all necessary hive components, or you can build your hive boxes from scratch. You can also order all the parts ready to be assembled, in which case all else you will need are a hammer, some nails and any color of exterior latex-based paint.

Order your bees early for the next year. Suppliers of bees commonly take orders for nucleus colonies, called nucs for short, or package bees in November and December, for delivery in April or May. If you wait too long to order, you will pay a premium or they may not have any bees to sell you. Several months before your colonies arrive, buy your hive components and other equipment. Have the hives assembled and placed on your selected site 30 days before your bees are scheduled to arrive.

Characteristics of a good colony

A strong population is crucial to a good bee colony. The queen lays a full brood pattern, skipping only a few cells, covering eight to 10 frames. You should see more worker brood than drone brood. The colony population reaches 75,000 bees during the summer, which includes 30,000 or more field bees. The bees cover all the frames in two hive bodies and the frames in one or more supers.

Drones appear in the spring but are forced out of the hive in the fall. About 1,000 of these male bees will live in the hive during the summer.

A good colony is docile when managed and shows little tendency to swarm, yet has workers that are good foragers. Each of the many strains of honey bees has different characteristics. The Italians are the most docile and are a good "starter" strain for a beginner.

Depending on the available nectar, each colony should produce between 40 and 80 pounds for itself to overwinter and 50 to 100 pounds of surplus honey each season that you can harvest. Harvest excess honey from the honey supers, leaving the honey in the brood boxes for the bees' winter food. The most common cause of colony demise in Missouri is winter starvation. Going into winter, a strong hive with five full frames of bees per brood box that contains a healthy queen and a minimal number of varroa mites will give the bees an excellent chance of survival. Leave a minimum of 40 to 80 pounds of honey per brood box for winter food and provide supplemental food (sugar water of 1 part water to 2 parts sugar) if necessary to bring the boxes up to weight.

Apiary location

Place the apiary near an abundant source of nectar and pollen. Trees and shrubs provide an excellent source of pollen, and plants in the daisy, legume and mint families provide excellent sources of nectar. In town, ornamental trees and plants usually provide ample sources of both. Ornamental plants in cities provide for an extended honey flow.

A good supply of water within a quarter mile of the hives is essential. Birdbaths, swimming pools, dog bowls and even lagoons are good sources of water for the bees. Bees actually prefer muddy water because of the extra minerals from the soil. A backyard apiary may need to offer a water source if none of the above are available. A shallow pan filled with water and some type of substrate, such as small rocks or floating pieces of wood, is an excellent addition to an apiary. Be sure to include a substrate for the bees to perch on as they are not good swimmers.

The apiary should face east or south with a northern windbreak. The location should be well-drained, away from any human or livestock paths, and hidden from unwanted visitors. Cattle and humans are naturally curious and might destroy or vandalize the hives, if tempted. The south face of a hillside is ideal, but bees will adapt to less-than-ideal locations.

Deciduous trees that partially shade the colony in summer afternoons and allow the sun to penetrate in winter are desirable. Place the apiary near an all-weather road because you will need to work the bees in all kinds of weather. When placing an apiary in town, face the hive entrance about a foot from a tall fence or shrub row so the bees will set their foraging flight pattern as high overhead as possible.

When placing your hives, provide a weed barrier — such as tin, gravel or recycled materials — for stability and ease of maintenance. Place the hives 18 inches above the ground on a stand, blocks or a pallet to minimize colony damage from skunks or rodents and, if you are using a screened bottom board, for dead pests to drop through.

Hives should be level from side to side but should be tilted slightly forward to prevent water from accumulating inside. Ventilate the hive through the top by propping open the telescoping lid with a stick to reduce humidity inside the hive. Moist conditions inside promote diseases.

Equipment

Due to bee health issues, buying new equipment is advisable. Much of the used bee equipment available has been inherited by nonbeekeeping family members, who may unknowingly be selling infected hives. Plus, frames and foundation need to be replaced every three to five years. Over time, the wax absorbs chemicals and contaminants that could be hazardous to larvae and young bees.

An eight- or 10-frame Langstroth hive is ideal for a beginning beekeeper (Figure 1). After you are comfortable keeping bees in this industry standard, you can experiment with other styles, such as top bar or horizontal deep hives. With the Langstroth, you can interchange and add standard hive equipment as needed. Note: Once you have chosen a frame supplier, you will need to get future frames from the same supplier because there is not an industry standard for frame construction and frames are not interchangeable between manufacturers.

A basic hive consists of the following parts:

- Two brood boxes, called "deeps," for the brood

- Two super boxes, called "mediums" or "supers," for excess honey stores

- Bottom board, either screened or solid reversible

- Entrance reducer

- Queen excluder (optional)

- Inner cover

- Telescoping lid

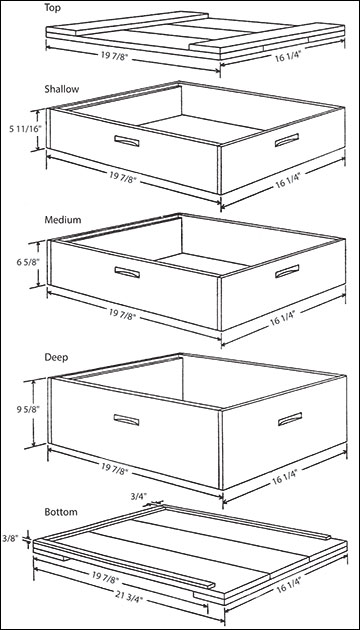

Depending on the amount of honey your hive produces, have additional medium supers ready to add to the hive as needed. The standard brood box, or deep, is 95/8 inches deep, 16-1/4 inches wide and 19-7/8 inches long. Deeps are for brood and for hive honey stores for the winter; this honey is not excess for harvesting but is winter food for the bees. Shallow supers, used mainly for comb honey production, are the same width and length but are only 5-11/16 inches deep. The medium super is 65/8 inches deep (Figure 2).

Hive boxes are built to contain 10 frames, but using nine frames is more convenient when working with bees, so remove one after the bees have completely pulled out all of the wax. Frames need to be in the center of the hive box, equally spaced with no more than 3/8 inch between their pulled wax foundations. Brood frames have small communication holes at the bottom that allow bee movement between sides. Move frames individually using the hive tool when you are working with your bees.

Foundation is available in a variety of options: wax, plastic, a combination of wax and plastic, and one-piece foundation-and-frame combinations. Bees prefer foundations of pure wax or of thin, wax-coated plastic to plastic foundations. Bees need to be fed or in a strong nectar flow before they will "draw out," or build their comb on, any foundation. Do not combine different types of foundation in a single brood box until the wax is completely pulled.

A strong colony will require at least two medium supers for honey storage. Add them when the brood boxes are 70 percent full of bees and there is a strong nectar flow in the spring.

Special foundations and tools are made for the production of cut comb honey. This unwired wax foundation is thinner than a regular wax foundation and is made mostly of wax cappings. Plastic rings are pressed to the foundation, and bees fill and cap the areas within and around the rings. Management practices for raising comb honey differ from simple honey production practices, and comb honey production is recommended for experienced beekeepers.

If you have 40 or more colonies, consider buying a motorized, or radial, extractor (Figure 3). Many beekeepers find that using a less expensive manual, or tangential, extractor works very well and serves their needs for years (Figure 4). Cut comb honey requires no investment in an extractor. With comb honey, only woodenware is stored, whereas comb storage requires fumigation.

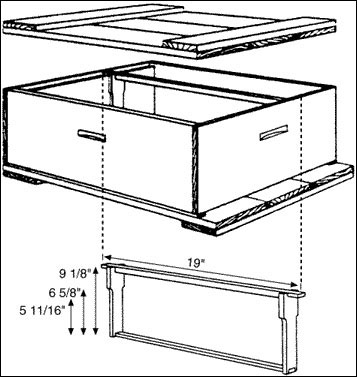

Figure 1

Figure 1

Wooden frames for holding the comb hang inside the body of a hive. Frames are sized for shallow, medium or deep hive bodies.

Figure 2

Figure 2

Parts of a beehive. Bees are reared in a brood chamber in the lowest level of the hive. Honey is stored in upper levels.

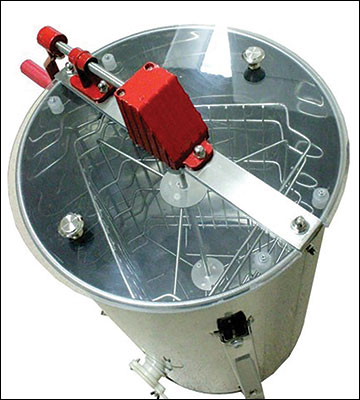

Figure 3

Figure 3

Radial extractor with frames placed in the reel like spokes of a wheel for removing honey from the comb (extractor shown here with cover removed). [E.H. Thorne (Beehives) Ltd.; used with permission].

Figure 4

Figure 4

Three-frame tangential extractor for extracting honey from the frames. (Maxant Industries; used with permission).

Installing bees

When installing bees from a package, gently shake the bees from the package into the desired hive. Place any bees remaining in the package on the ground in front of the hive; they should find their way into the hive eventually. The queen will be in a cage that is corked on both ends. Remove the cork that is on the end with candy. Place this cage candy-side-up between two center frames of the hive. The bees will eat the candy within a couple of days, releasing the queen into the hive.

Installing a nuc is much easier. Nucs are typically provided on five frames. Carefully insert the frames into the center of your hive. Insert empty frames to fill out the hive.

Honey plants

Spring honey plants in Missouri include (in approximate order of importance) clovers, sweet clovers, other legumes, tulip poplar trees, dandelions, maple trees, locust trees, willow trees, basswood trees, fruit trees and berry plants. Trees, sorghum and other grasses are important pollen sources.

In summer and fall, bees find nectar and pollen in soybeans, cotton, garden plants, various ornamentals, asters, goldenrod, milkweed, morningglory, smartweed, sumac and sunflowers. Bees will use thousands of species. Those listed here may not be the most important in your area.

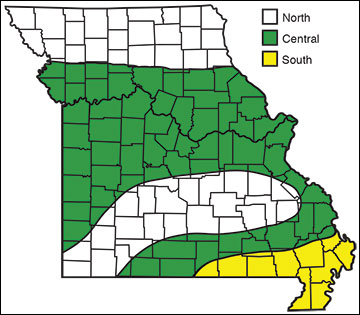

Plants bloom at different times in different places. According to Hopkins' Bioclimatic Law, in North America east of the Rockies, a 400-foot increase in elevation, a 4-degree change in latitude north or a 10-degree change in longitude east will cause any given biological event to occur four days later in the spring or four days earlier in the fall. If tulip poplars begin to bloom in the Bootheel region around May 15, they should bloom five days later in Columbia and 10 days later in Lancaster on the Iowa border (Figure 5).

Moving bees to new nectar sources can be beneficial. About July 1, you might wish to move the bees from town to a soybean field, with the owner's permission. Always move the bees at least three miles from their previous site and during the dark. The bees will orient themselves to the new location when the hive is opened.

Figure 5

Figure 5

Missouri planting regions.

Disease prevention

To prevent disease, always buy new equipment, and replace frames and foundations every three to five years. Have enough hive tools available that you can use one per bee yard to avoid cross-contamination.

Foulbrood

European and American foulbrood (EFB and AFB) are bacterial diseases of bees. AFB spreads to larva through spores and can quickly kill a colony. Treatment for American foulbrood is usually total hive destruction because the disease is difficult to control with medicine and the spores will live in brood boxes for decades

The bacteria that causes EFB does not produce spores, but multiplies in the larva's gut after ingested. EFB is less likely to spread in colonies with strong nectar flow. Treatment with antibiotics might clear up an infected colony, and all equipment will need to be cleaned to prevent reinfection.

Signs of foulbrood include a foul smell and a spotty brood pattern. Diagnostic kits that test for foulbrood and give immediate results can be purchased from beekeeping suppliers.

Nosema disease

Two types of nosema fungi are now known to cause disease in bees. Nosema apis is primarily a problem in winter and early spring, and Nosema ceranae in summer and fall. Both fungi cause disease in adult bees and spread by spores. Nosema is difficult to identify and diagnose because there are no symptoms that are specific to it. Only a microsopic exam can provide a reliable diagnosis.

The best control measures for nosema are a healthy diet of pollen and nectar, and moisture control in the hives. Antibiotics can be purchased from beekeeping supply companies, but use them only when necessary, because bees can develop resistance to them. Do not use antibiotics during the honey production season. Keep a good supply of food for the colony at all times. Most colonies that do not survive the winter die in March of starvation or of nosema, due to moisture issues inside the hive during the cold winter months.

Mite control

Acarapis woodi (Rennie)

The honey bee tracheal mite, Acarapis woodi (Rennie), was found in Jackson County, Missouri, on April 17, 1986. These mites are now present in every Missouri county. First discovered in 1921, tracheal mites were a probable cause of Isle of Wight disease. Most honey bees on that island were killed by this mite. All surviving bees were tracheal mite–resistant. It is best to use honey bee queens and package bees that are resistant to tracheal mites. The Italian bee strain, Apis mellifera ligustica, is susceptible to tracheal mites. Resistance is documented in carniolan bees, Apis mellifera carnica. Currently, resistance is developing or being developed in other races of honey bee.

There are two fumigant treatments for tracheal mites, Mite-a-Thol and Mite-Away II, and a grease paddy method. Treating colonies continuously with oil-sugar patties has been proven to depress mite populations. These patties are made of 3 parts sugar to 1 part vegetable shortening, with 1/2 pound of honey and 1 ounce of peppermint flavoring mixed in as bee attractants. The residual grease on the bees smothers mites. The use of resistant bees and oil-sugar patties will give sufficient control of tracheal mites.

Varroa jacobsoni Oudemans

The Varroa mite is the most severe problem in beekeeping. Varroa mites were detected in West Plains and Hayti, Missouri, in 1989. These mites have since spread throughout the state. Without treatment, a colony of bees will die from varroa parasitism within 36 months. Use of resistant bees, such as the Russian strain, is the only long-term solution to varroosis in honey bees.

In the interim, monitoring and treatment are the best management practices. Monitor mite populations by counting mites using a jar or sticky board method. For the jar method, about 300 bees are captured in a mason jar with 1/3 cup of powdered sugar. Rolling the bees in the sugar causes the mites to drop off. The sticky board method uses a screened bottom board with a rear-access removable tray that catches any mites that are brushed off, let go, or slip off hive components and fall to the bottom board.

Treatments include dusting the hive components with powdered sugar, drone trapping, or chemical treatments. With drone trapping, two frames are used to trap out mites by using drones as bait. As the drone comb is replaced, the mite population is reduced. The chemical treatments come in the form of fumigants, such as Mite-Away Quick Strips; essential oils; and miticides, such as Apistan, Apiguard and CheckMite. The miticides require contact with the honey bee and then the hitchhiking mite. These chemicals should be used as a last resort because they can decrease egg laying and drone reproductive health, and can be absorbed into the beeswax. If required, colonies can be treated with fluvalinate (Apistan), organophosphate (CheckMite), or formic acid–impregnated plastic strips (Mite-Away Quick Strips) twice each year, before and after honey season. Quick Strips have a treatment period of just seven days, reducing the opportunity for future resistance. Alternating Apistan with Apiguard will also reduce the incidence of resistance. As always, follow manufacturer's instructions for each chemical treatment selected.

Monitor for mites every other month. If you are not sure if you have an infestation, ask a beekeeping friend or go to your local MU Extension center for identification of mites. If you find one mite, you can assume 500 are present.

Note

The University of Missouri intends no endorsement of products named in this guide nor criticism of similar products that are not mentioned.

Wax moth control

Wax moths are a destructive beehive pest. A strong colony with a large population of young housekeeping bees is the best defense against them. Another control measure is to fumigate small amounts of equipment in large plastic garbage bags.

Wax moth colonies do not thrive in light and fresh air, so a rack that exposes hive components to ventilation and protects them from rain is ideal. You can also kill a small population of eggs, larvae and pupae by placing the entire super in a large freezer for two days. As a last resort, you can fumigate with paradichlorobenzene moth crystals (not naphthalene or moth balls) before placing them back on. To fumigate, stack equipment as on a hive, seal up all air holes, and put the stack on a flat surface. Put a piece of notebook paper over the top frames to hold the fumigant on the stack. Put a sheet of plastic over the fumigant, and cover the entire stack with a flat board or telescoping cover. Seal side cracks between the supers with tape. Two tablespoons of paradichlorobenzene will fumigate eight supers or four hive bodies. Before using the supers next season, set the frames outside one full week to air out.

Hive beetle control

Small hive beetles can be destructive to a bee colony. The larvae tunnel through the comb and leave excrement that causes the honey to ferment and become runny. Clusters of eggs laid in areas where bees cannot tunnel lead to thousands of aggressive larvae seeking pollen, bee larvae and pupae to eat. Maintaining a large, strong colony is the best defense for this pest. Monitoring for and trapping beetles can reduce large numbers in a hive.

Insecticide drift

You are responsible for protecting your colonies. Confine the colonies with ventilated cloth for three days during heavy insecticide spraying, but bees must be allowed to fly on the fourth day.

Familiarize yourself with spray practices and chemicals used around your apiary. Whenever possible, locate colonies away from frequently sprayed fields. If this is impossible, an upwind location is better than a downwind location.

Glossary

- Apiary

Group of bee colonies in one location; bee yard. - Apiculture

The science and art of studying and using honey bees for the benefit of humans. - Beeswax

Wax secreted from glands on the underside of bee abdomens and then molded to form honeycomb. - Brood

Immature or developing stages of bees; includes eggs, larvae (unsealed brood) and pupae (sealed brood). - Brood chamber

The area of the hive where the brood is reared; usually the lowermost hive bodies; contains brood comb. - Brood nest

The area of hive where bees are densely clustered and brood is reared. - Colony

An entire honey bee family or social unit living together in a hive or other shelter. - Colony collapse disorder

A pathological condition affecting a large number of honey bee colonies, in which various stresses may lead to the abrupt disappearance of worker bees from the hive, leaving only the queen and newly hatched bees behind and thus causing the colony to stop functioning. - Comb

A beeswax structure composed of two layers of horizontal cells sharing their bases, usually within a wooden frame in a hive. The words "comb" and "frame" are often used interchangeably; for example, a frame of brood, a comb of brood. - Comb honey

Honey in the sealed comb in which it was produced. It is also called section comb honey when produced in thin wooden frames (sections) and comb honey when produced in shallow frames. - Draw

To shape and build, as to draw comb from a sheet of foundation. - Dysentery

A malady of adult bees marked by an accumulation of excess feces or waste products, and by their release in and near the hive. - Field bee, or forager

Worker bee that travels outside the hive to collect nectar, pollen, water and propolis, a waxy substance that bees use in the hive as cement. - Foundation, or comb foundation

A thin sheet of beeswax embossed on each side with the cell pattern, on which the bees build a honeycomb. - Foulbrood

A general name for infectious diseases of immature bees that cause them to die and their remains to smell bad. The term most often refers to American foulbrood. - Frame

A wooden rectangle that surrounds the comb and hangs in the hive. It may be called Hoffman, Langstroth or self-spacing because of differences in size and widened end-bars that provide a bee space between the combs. - Hive body

A single wooden rim or shell that holds a set of frames. When used for the brood nest, it is called a brood chamber; when used above the brood nest for honey storage, it is called a super. It may be of various sizes and adapted for comb honey sections. - Honey flow

Period when bees are collecting nectar in plentiful amounts from plants and storing a surplus of honey. - House bee

A young worker bee, 1 day to 2 weeks old, that works only in the hive. - Langstroth hive

A hive with movable frames. The bee space around the frames allows you to move the frames. It was invented by L.L. Langstroth. - Nectar flow

Period when nectar is available. - Nosema disease

An infectious disease of adult bees caused by the fungus Nosema apis or Nosema ceranae - Nuc

Short for nucleus colon. A small bee colony, complete with a queen or the means to make one, bees, brood and food. - Package bees

Two to 4 pounds of worker bees, usually with a queen, in a screen-sided wooden cage with a can of sugar syrup for food. - Paradichlorobenzene (PDB)

A white crystalline substance used to fumigate combs and repel wax moths. - Pollen

Male reproductive cells of flowers collected and used by bees as food for rearing their young. It is the protein part of the diet. Frequently called bee bread when stored in cells in the colony. - Pollen substitute

Mixture of water, sugar and other material, such as soy flour or brewer's yeast, used for bee feed. - Propolis

A mixture of tree resins and enzymes used by bees as a cement and to fill in small spaces in the hive. - Queen

Sexually developed female bee. The mother of all bees in the colony. - Queen right

A colony with a queen that is capable of laying fertile eggs. - Rendering wax

Melting old combs and wax cappings and removing refuse to partially refine the beeswax. May be put through a wax press. - Super

A hive body used for honey storage above the brood chambers of a hive. - Swarm

A group of worker bees and a queen (usually the old one) that leave the hive to establish a new colony; a word formerly used to describe a hive or colony of bees. - Telescoping cover

A hive cover, used with an inner cover, that extends downward several inches on all four sides of a hive. - Uniting

Combining one honey bee colony with another. - Wax moth

An insect whose larvae feed on and destroy honey bee combs. - Wired foundation

Comb foundation with vertical wires embedded in it for added strength. - Wiring

Installing tinned wire in frames as support for combs.

Beekeeping suppliers, organizations and resources

Suppliers

- Betterbee

8 Meader Road,

Greenwich, NY 12834

800-632-3379

http://betterbee.com - Dadant and Sons

51 S. Second St.,

Hamilton, IL 62341

888-922-1293

http://dadant.com - GloryBee

P.O. Box 2744,

Eugene, OR 97402

800-456-7923

http://glorybee.com - Honey Bee Ware

N1829 Municipal Drive,

Greenville, WI 54942

920-779-3019

http://honeybeeware.com - Mann Lake Ltd.

501 S. First St.,

Hackensack, MN 56452

800-880-7694

http://mannlakeltd.com - Kelley Beekeeping Co.

P.O. Box 240,

Clarkson, KY 42726

800-233-2899

https://kelleybees.com

Organizations

Local

As of March 2016, Missouri had 35 local beekeeping associations. See the Missouri State Beekeepers Association website for a list of the local associations and information on when and where they meet: http://mostatebeekeepers.org/local-clubs.

Regional

Each of the regional beekeeping societies listed below holds an annual meeting or conference. EAS also publishes a quarterly newsletter.

- Eastern Apicultural Society of North America (EAS)

http://easternapiculture.org - Heartland Apicultural Society

http://heartlandbees.org

State

- The Missouri State Beekeeping Association holds an annual conference, publishes a bimonthly newsletter and offers robust member-exclusive content on its website: http://mostatebeekeepers.org

National

- American Beekeeping Federation

http://abfnet.org - American Honey Producers Association

https://www.ahpanet.com/ - National Honey Board

http://honey.com - Pollinator Partnership

http://pollinator.org

Partnership associations

- FieldWatch, a nonprofit organization that operates DriftWatch, a mapping tool for communication among beekeepers, farmers and pesticide applicators on the presence of apiaries and pesticide-sensitive crops

http://fieldwatch.com - Honey Bee Health Coalition, a group of almost 40 food, agriculture, government and conservation organizations and agencies focused on achieving and supporting a healthy population of honey bees and other pollinators

http://honeybeehealthcoalition.org - Master Pollinator Steward Program, an MU Extension program developed to educate the general public about the plight of pollinators and teach them steps they can take to benefit pollinators

https://extension.missouri.edu/programs/master-pollinator-steward - Pollinator Stewardship Council, a nonprofit group that strives to protect pollinators vital to a sustainable and affordable food supply from the adverse effects of pesticides

http://pollinatorstewardship.org

Periodicals

- American Bee Journal

217-847-3324

info@americanbeejournal.com

http://americanbeejournal.com - Bee World

011-44-29-2037-2409,

beeworld@ibra.org.uk

https://ibra.org.uk/bee-world - American Beekeeping Federation Newsletter

and ABF E-Buzz

404-760-2875

info@abfnet.org

http://abfnet.org

References

- The ABC and XYZ of Bee Culture: An Encyclopedia of Beekeeping (40th edition). Roger Morse, A.I. Root Company, Medina, Ohio (1990).

- Anatomy of the Honey Bee. R.E. Snodgrass, Comstock Books, Ithaca, N.Y. (1956).

- The Archaeology of Beekeeping. Eva Crane, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, N.Y. (1983).

- Beekeeping at Buckfast Abbey. Brother Adam, available from Wicwas Press, Cheshire, Conn.

- Beekeeping in the United States. USDA Agricultural Handbook #335, Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C.

- The Biology of the Honey Bee. Mark L. Winston, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass. (1987).

- The Dancing Bees: An Account of the Life and Senses of the Honey Bee. Karl von Frisch, translated from the German by Dora Isle and Norman Walker, second edition, Methuen, London (1966).

- The Hive and the Honey Bee. Edited by Dadant and Sons Inc., Hamilton, Ill. (1991).

- Honey Bees and Beekeeping. Keith Deleplane, University of Georgia, available from Dadant and Sons Inc. Hamilton, Ill. (1995).

- Honey Bee Pests, Predators, and Diseases. Roger A. Morse and Richard Nowagrodzki, editors, Wicwas Press, Cheshire, Conn. (1990).

- Queen Rearing and Bee Breeding. Harry H. Laidlaw Jr. and Robert E. Page, Wicwas Press, Cheshire, Conn. (1997).

- Queen Rearing Simplified. Vince Cook, available from Dadant and Sons Inc., Hamilton, Ill.