For some time, we have known that development results from the dynamic interplay of nature and nurture. From birth on, we grow and learn because our biology is programmed to do so and because our social and physical environment provides stimulation.

New research on early brain development provides a wonderful opportunity to examine how nature and nurture work together to shape human development. Through the use of sophisticated technology, scientists have discovered how early brain development and caregiver-child relationships interact to create a foundation for future growing and learning.

Note

For this guide, the word caregiver includes anyone who cares for young children, such as parents, grandparents, child care providers or preschool teachers.

The nature of early brain development

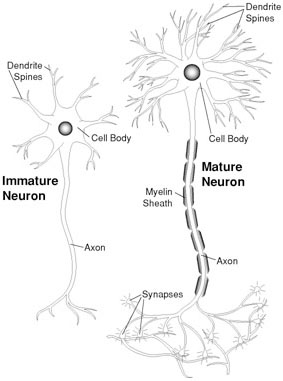

At birth, the human brain is still preparing for full operation. The brain's neurons exist mostly apart from one another. The brain's task for the first 3 years is to establish and reinforce connections with other neurons. These connections are formed when impulses are sent and received between neurons. Axons send messages and dendrites receive them. These connections form synapses. (Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Neurons mature when axons send mesages and dendrites receive them to form synapses.

As a child develops, the synapses become more complex, like a tree with more branches and limbs growing. During the first 3 years of life, the number of neurons stays the same and the number of synapses increases. After age 3, the creation of synapses slows until about age 10.

Between birth and age 3, the brain creates more synapses than it needs. The synapses that are used a lot become a permanent part of the brain. The synapses that are not used frequently are eliminated. This is where experience plays an important role in wiring a young child's brain. Because we want children to succeed, we need to provide many positive social and learning opportunities so that the synapses associated with these experiences become permanent.

How the social and physical environments respond to infants and toddlers plays a big part in the creation of synapses. The child's experiences are the stimulation that sparks the activity between axons and dendrites and creates synapses.

The nurture of early brain development

Infants and toddlers learn about themselves and their world during interactions with others. Brain connections that lead to later success grow out of nurturant, supportive and predictable care. This type of caregiving fosters child curiosity, creativity and self-confidence. Young children need safety, love, conversation and a stimulating environment to develop and keep important synapses in the brain.

Caring for infants and toddlers is mostly about building relationships and making the most of everyday routines and experiences. The Creative Curriculum for Infants and Toddlers (Dombro, Colker and Dodge, 1997) says that during the first 3 years of life, infants and toddlers look to caregivers for answers to these questions:

- Do people respond to me?

- Can I depend on other people when I need them?

- Am I important to others?

- Am I competent?

- How should I behave?

- Do people enjoy being with me?

- What should I be afraid of?

- Is it safe for me to show how I feel?

- What things interest me?

Learning with all five senses

During the first 3 years of life, children experience the world in a more complete way than children of any other age. The brain takes in the external world through its system of sight, hearing, smell, touch and taste. This means that infant social, emotional, cognitive, physical and language development are stimulated during multisensory experiences. Infants and toddlers need the opportunity to participate in a world filled with stimulating sights, sounds and people.

Create a multi-sensory environment

- Experiment with different smells in the classroom. Try scents like peppermint and cinnamon to keep children alert and lavender to calm them down.

- Remember that lighting affect alertness and responsiveness. Bright lights keep infants and toddlers alert; soft lights help infants and toddlers to calm down.

- Expose infants and toddlers to colors that stimulate the brain. Use colors like pale yellow, beige, and off-white to create a calm learning environment; use bright colors such as red, orange, and yellow to encourage creativity and excitement.

- Use quiet and soft music to calm infants and toddlers and rhythmic music to get them excited about moving.

- Create a texture book or board that includes swatches of different fabrics for infants and toddlers to feel.

- Describe the foods and drinks that you serve infants and toddlers and use words that are associated with flavor and texture ("oranges are sweet and juicy;" "lemon yogurt is a little sour and creamy").

Thinking and feeling

Before children are able to talk, emotional expressions are the language of relationships. Research shows that infants' positive and negative emotions, and caregivers' sensitive responsiveness to them, can help early brain development. For example, shared positive emotion between a caregiver and an infant, such as laughter and smiling, engages brain activity in good ways and promotes feelings of security. Also, when interactions are accompanied by lots of emotion, they are more readily remembered and recalled.

Early brain development: when things go wrong

Early development does not always proceed in a way that encourages child curiosity, creativity and self-confidence. For some children, early experiences are neither supportive nor predictable. The synapses that develop in the brain are created in response to chronic stress, or other types of abuse and neglect. And, when children are vulnerable to these risks, problematic early experiences can lead to poor outcomes.

For example, some children are born with the tendency to be irritable, impulsive and insensitive to emotions in others. When these child characteristics combine with adult caregiving that is withdrawn and neglectful, children's brains can wire in ways that may result in unsympathetic child behavior. When these child characteristics combine with adult caregiving that is angry and abusive, children's brains can wire in ways that result in violent and overly aggressive child behavior. If the home environment teaches children to expect danger instead of security, then poor outcomes may occur.

In these cases, how do nature and nurture contribute to early brain development? Research tells us that early exposure to violence and other forms of unpredictable stress can cause the brain to operate on a fast track. Such overactivity of the connections between axons and dendrites, combined with child vulnerability, can increase the risk of later problems with self-control. Some adults who are violent and overly aggressive experienced erratic and unresponsive care early in life.

Adult depression can also interfere with infant brain activity. When caregivers suffer from untreated depression, they may fail to respond sensitively to infant cries or smiles. Adult emotional unavailability is linked with poor infant emotional expression. Infants with depressed caregivers do not receive the type of cognitive and emotional stimulation that encourages positive early brain development.

Programs that work

When children have less-than-optimal experiences early in life, there is hope for the future. Understanding how brain development is affected by negative experiences gives us the opportunity to intervene and to prevent future difficulties. And, because we know about healthy early brain development and the experiences that infants and toddlers need, programs have been designed to help children develop the necessary skills that they may not have developed earlier.

In Missouri, the Parents as Teachers (PAT) program provides information about child development to parents whose children are between birth and age 5. The information is delivered by well-prepared parent educators during home visits and parenting classes, and through referrals to other agencies. An evaluation of the program showed that PAT children scored higher on measures of intellectual and language ability than children whose parents did not participate in PAT. PAT is available to all families in Missouri and is a good example of how caregiver education about child development can help children throughout their lives.

Advocating for children

Early brain development research reinforces an important message about children: From birth on, children are ready and eager to learn and grow. Taking advantage of this situation means that all caregivers need to understand the importance of the early years and to recognize appropriate methods for stimulating children's learning and growth. Providing educational opportunities to parents, grandparents, child care providers and other caregivers is a step in the right direction to guarantee productive early years. Sharing this message with policy makers is another strategy for ensuring that infants, toddlers, and young children and their caregivers receive the necessary education and support.

Early brain development and child care providers

Here are some tips for how to effectively establish relationships with infants and toddlers and to promote early brain development:

- Learn to read the physical and emotional cues of the infants and toddlers in your care. Recognize the individuality of each child and sensitively respond to these differences.

- Assign a primary caregiver to each infant and toddler in your program to work with the child and his/her family.

- Observe and record the infant and toddler behaviors that are indicative of early brain development. Share these observations with other caregivers who play an important role in the children's lives.

- Accept infants' and toddlers' strong emotions as signs of their desire to communicate with you and the world. Respond quickly and appropriately to these communications; give meaning to these emotional communications.

- Find a balance between being overinvolved and being underinvolved; recognize the child's current developmental status and create opportunities for each child to reach beyond his/her abilities.

Caregivers and infants together

Early brain development research reinforces the importance of caregiver sensitivity and responsiveness to infant behaviors and needs. What do insensitive and unresponsive caregiver-infant interactions look like? What do sensitive and responsive caregiver-infant interactions look like?

Below are some real-life examples of caregivers interacting with their 4-month-old babies. Although these are only brief examples of caregiver-infant interactions, consider what is happening to the baby's development if most interactions are like these ones. As you read each example, put yourself in the baby's position and "See the world through the eyes of the child." Ask yourself:

- How sensitive is the caregiver to the baby's needs and abilities?

- How responsive is the caregiver to the baby's behaviors and communications?

- How does the caregiver stimulate the baby's senses?

In this example, the caregiver is generally out of touch with the baby. The caregiver's words are mostly discouraging; the caregiver leaves the baby with the toys out of the baby's reach; the caregiver does not recognize the baby's frustration or try to help the baby calm herself down; and, the caregiver does little that stimulates the baby's five senses. Imagine daily life for this baby if most of her interactions are like this one. How are her senses being stimulated? What connections are being wired in her brain?

In this example, the caregiver enthusiastically greets the baby after she returns to the room; the caregiver stimulates the baby's senses with her tickling and toy rattle; and, she encourages the baby's physical development when she leaves the rattle for the baby to hold. When the rattle falls and hits the baby, the caregiver sensitively responds, gives meaning to the baby's cries and shares physical affection in an effort to soothe the baby. Consider how these experiences help an infant develop trust in the world.

Observations from Isabella, Russell A. 1993. Origins of attachment: Maternal interactive behavior across the first year. Child Development, 64, 605-621.

References

- Caldwell, Bettye. May 1998. "Early experiences shape social development." Child Care Information Exchange: 53-59.

- Dombro, Amy Laura, Laura J. Colker and Diane Trister Dodge. 1997. The Creative Curriculum for Infants and Toddlers. Washington, DC: Teaching Strategies, Inc.

- Gilkerson, Linda. May 1998. "Brain care: Supporting healthy emotional development." Child Care Information Exchange: 66-68.

- Healthy Child Care America. January 1999. Early brain development and child care. American Academy of Pediatrics.

- Healy, Jane M. 1994. Your child's growing mind: A practical guide to brain development and learning from birth to adolescence. New York: Doubleday.

- Isabella, Russell A. 1993. "Origins of attachment: Maternal interactive behavior across the first year." Child Development, 64: 605-621.

- Karr-Morse, Robin, and Meredith S. Wiley. 1997. Ghosts from the nursery: Tracing the roots of violence. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press.

- Kotulak, Ronald. 1997. Inside the brain: Revolutionary discoveries of how the mind works. Kansas City, Mo.: Andrews McMeel Publishing

- Lally, J. Ronald. May 1998. "Brain Research, Infant Learning, and Child Care Curriculum." Child Care Information Exchange: 46-48.

- Rogers, Adam, Pat Wingert, and Thomas Hayden. May 3, 1999. "Why the Young Kill." Newsweek: 32-35.

- O'Donnell, Nina Sazer. March 1999. "Using early childhood brain development research." Child Care Information Exchange: 58-62.

- Schiller, Pam. May 1998. "The thinking brain." Child Care Information Exchange: 49-52.

- Shore, Rima. 1997. Rethinking the brain: New insights into early development. New York: Families and Work Institute.

- University of Pittsburgh, Office of Child Development. Spring, 1998. "Brain development: The role experience plays in shaping the lives of children." Children, Youth, and Family Background, Report 12. Pittsburgh: University Center for Social and Urban Research.

- Weikert, Phyllis S. May 1998. "Facing the challenge of motor development." Child Care Information Exchange: 60-62.

- Willis, Clarissa. May 1998. "Language development: A key to lifelong learning." Child Care Information Exchange: 63-65.