Forages are the foundation of a successful pasture-based dairy. So when forage yield or quality drops, so does milk production. Successful forage systems consider more than annual forage yield or milk production per acre. They also consider plant persistence, long-term sustainability, cost per unit of milk produced and, ultimately, profitability. Graziers should consider all of these factors before developing a forage system for their farms.

From a biological perspective, there are three important concepts to understand when planning a forage system:

- Forage yield and yield distribution

- Forage quality

- Stand persistence or reliability

Although these three concepts are interrelated, the following discussion examines each of them separately.

Forage yield and yield distribution

Many producers consider yield the most important attribute for any forage. Clearly, forages that do not yield well cannot be part of a productive forage program. But annual yield alone should not be used to select forages for pasture-based systems. For these systems, distribution of yield throughout the growing season is far more important than annual yield.

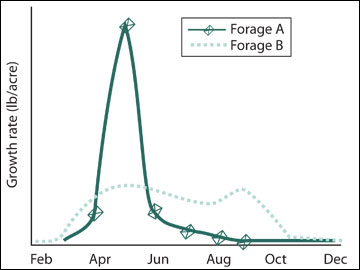

As an example, consider the two forages in Figure 1. Notice that forage A and forage B have the same annual yield. However, forage A produces 80 percent of its growth in May while forage B has a more even distribution of yield throughout the growing season. Forage A might be great for hay production, but forage B would be far superior for grazing all season long.

Although forages vary in their seasonal yield distribution, no forage is productive during all seasons of the grazing year. An important principle for developing a productive forage program for a pasture-based dairy is using the inherent differences in seasonal growth patterns to provide grazing for as much of the year as possible. This publication simplifies this process by providing diagrams that show the typical yield distribution for several forages used in Missouri. Use these diagrams to build a forage system that provides grazing for as much of the season as possible.

Figure 1. Yield distribution of two unique forages.

Figure 1. Yield distribution of two unique forages.

Forage quality

Almost any “mainstream” forage can be managed for dairy-quality feed. Some forages inherently contain more energy and protein than others, but nearly any can be managed to produce milk from pasture. The overriding concept here is that forage must be kept in a vegetative stage of growth to be of acceptable quality for milk production. In practice, this means that most cool-season grasses and short warm-season grasses such as bermudagrass and caucasian bluestem should be grazed when they reach 5 to 8 inches in height. Tall warm-season grasses should be grazed when they are 10 to 14 inches high. Waiting any longer than this will reduce forage quality as well as milk production.

Keeping the grass in a vegetative stage of growth may be difficult to do on a whole-farm basis, especially in late spring. During late spring, grass growth often exceeds what the milking herd can consume. Paddocks that become more mature than the guidelines mentioned above should be “skipped” in the rotation and the milking herd “moved forward” to less mature paddocks. The “skipped” or mature paddocks should be harvested for hay or silage, or grazed by dry cows or other nonlactating livestock as soon as is feasible. These paddocks can again be part of the rotation for the milking herd after the grass has been harvested and shows 5 to 8 inches of regrowth.

Stand persistence or reliability

Many producers undervalue long-term stand persistence of many perennial forage species. Considering that it costs $75 to $250 per acre to establish a new forage, it pays to make stands last.

Persistence mechanism

Although we tend to equate persistence with the survival of individual plants, from a producer’s perspective we are more interested in the “persistence of yield or productivity.” In some cases, stand persistence may be the survival of individual plants, but in other instances it may involve the natural reseeding capability of a species (for example, annual lespedeza or crabgrass). What is important to know is the “mechanism” each species uses to persist. For instance, birdsfoot trefoil is a short-lived perennial legume. It is short-lived because it is susceptible to several root and crown rot diseases. But if birdsfoot trefoil is given a 45- to 60-day rest period to reseed every other year, stands can last almost indefinitely. Its persistence mechanism is reseeding. Similarly, annual lespedeza and crabgrass pastures can act almost as perennials if given a reseeding period each year.

On the other hand, a species such as alfalfa does not reseed well in Missouri. Instead, it relies on the survival and development of the individual plants that were seeded. Thus, its persistence mechanism is plant longevity. Species that use plant longevity to persist must be carefully selected so that adapted varieties are planted. For these types of forages, it is most important to select varieties that can tolerate less-than-ideal soil or environmental conditions or that show resistance to common diseases or insects.

Vegetative propagation is another persistence mechanism. An example of a plant that uses this mechanism is smooth bromegrass. Smooth bromegrass has rhizomes, or “underground runners,” that continually develop new plants to thicken the stand. Forages that use this persistence mechanism are often among the easiest to maintain.

In summary, understanding what mechanism your forages use to persist is the first key to managing for maximum stand life.

Soil environment

Another factor that influences stand persistence is the soil environment. The most important aspects of the soil environment are the depth, drainage and fertility of your soils. For example, alfalfa is one of the most productive and nutritious forages available on well-drained and fertile soils. However, it does not survive well on poorly drained soils and does not tolerate low soil fertility. In this situation, a better choice might be to plant reed canarygrass and manage it to provide dairy-quality feed.

Picking a species adapted to your soil environment is key to a persistent forage. Table 1 lists the tolerance of many forages to poor soil drainage and low soil fertility. Use it as a guide to choose a species that matches the soil environment of your operation.

Cold hardiness and drought tolerance

Forages also should be selected for cold hardiness and drought tolerance. Many forages might survive a mild winter or a wet summer, but what happens when growing conditions are less than ideal? Under these conditions, differences in forage species become apparent. For instance, if we have a wet, cool summer, both timothy and orchardgrass persist quite well. However, when the weather turns dry, timothy does not persist as well because it has a shallower root system. Table 1 should be helpful in selecting a forage that can withstand less than ideal growing conditions.

Management

Management also plays a vital role in stand persistence. Almost no forage can survive poor management and be productive. The major management factors that influence stand persistence are grazing frequency, residual leaf area after grazing and planned rest periods for reseeding or fall growth. For more information on management factors that influence stand persistence, see MU Extension publication M184, Design and Management of a Dairy Pasture.

Summary

Several forages are available to graziers. Selecting a set of forage species based on yield distribution, forage quality and stand persistence is key to building a successful forage system for a pasture-based dairy. Before planning a forage system, become familiar with the key characteristics of the forages adapted to your region. The following pages provide an overview of the advantages and disadvantages of perennial and annual forages. They also lay a foundation for understanding how to put these species to work in your pasture-based dairy.

Table 1. Quick guide to forage species adaptability.

| Species | Yield potential | Tolerance to poor drainage | Tolerance to low soil fertility | Tolerance to drought | Tolerance to heat | Overwintering ability | Suitability for wildlife habitat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cool-season grasses | |||||||

| Annual ryegrass | Very good | Very good | Poor | Fair | Poor | Fair | Fair |

| Kentucky bluegrass | Fair | Very good | Very good | Poor | Poor | Excellent | Good |

| Orchardgrass | Very good | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good | Very good |

| Perennial ryegrass | Good | Good | Fair | Poor | Poor | Fair | Good |

| Prairiegrass | Good | Fair | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good |

| Reed canarygrass | Excellent | Excellent | Very good | Very good | Good | Excellent | Fair |

| Small grains | Very good | Very good | Good | Good | Fair | Very good | Good |

| Smooth bromegrass | Good | Good | Fair | Very good | Good | Excellent | Fair |

| Tall fescue (endophyte-free) | Very good | Very good | Good | Fair | Good | Very good | Fair |

| Tall fescue (endophyte-infected) | Very good | Very good | Very good | Very good | Very good | Very good | Poor |

| Timothy | Fair | Good | Very good | Poor | Poor | Excellent | Very good |

| Warm-season grasses | |||||||

| Bermudagrass | Excellent | Fair | Fair | Good | Excellent | Fair | Poor |

| Big bluestem | Very good | Very good | Very good | Excellent | Very good | Very good | Good |

| Corn | Excellent | Very good | Poor | Fair | Very good | — | Fair |

| Crabgrass | Good | Very good | Very good | Good | Excellent | — | Fair |

| Eastern gamagrass | Very good | Excellent | Good | Very good | Very good | Very good | Good |

| Indiangrass | Very good | Good | Very good | Excellent | Very good | Very good | Very good |

| Old World bluestem | Very good | Good | Excellent | Very good | Very good | Good | Fair |

| Pearlmillet | Very good | Very good | Good | Excellent | Very good | — | Fair |

| Sorhum-sundangrass | Excellent | Very good | Fair | Very good | Very good | — | Fair |

| Switchgrass | Excellent | Very good | Very good | Very good | Very good | Very good | Good |

| Legumes | |||||||

| Alfalfa | Excellent | Poor | Poor | Excellent | Very good | Excellent | Very good |

| Birdsfoot trefoil | Good | Very good | Very good | Good | Good | Excellent | Poor |

| Clover, alsike | Fair | Excellent | Good | Poor | Poor | Very good | Fair |

| Clover, crimson | Fair | Fair | Good | Good | Fair | Fair | Good |

| Clover, kura | Good | Very good | Good | Very good | Good | Excellent | Fair |

| Clover, red | Very good | Good | Good | Good | Good | Very good | Good |

| Clover, white | Good | Very good | Good | Poor | Poor | Excellent | Good |

| Hairy vetch | Good | Very good | Good | Good | Good | Fair | |

| Lespedeza, annual | Poor | Very good | Excellent | Very good | Very good | — | Good |

| Other | |||||||

| Brassica species | Good | Poor | Good | Very good | Very good | Poor | Poor |

Table 2. Quick guide to forage species establishment.

| Species | Ease of establishment | Seeding rate for pure stands (lb/acre)1 | Seeding dates | Preferred seeding depth (inches) | Months from seeding to first grazing | Preferred soil pH | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Broadcast | Drilled | Spring | Fall | |||||

| Cool-season grasses | ||||||||

| Annual ryegrass | Easy | 30 | 25 | — | 8/15 to 9/15 | ¼ | 2 | 5.5 to 7.5 |

| Kentucky bluegrass | Easy to medium | 10 to 15 | 8 to 10 | 2/1 to 4/1 | — | ¼ | 2 to 4 | 5.5 to 7.0 |

| Orchardgrass | Medium | 15 to 20 | 10 to 15 | 3/15 to 4/30 | 8/15 to 9/15 | ¼ to ½ | 3 to 6 | 5.5 to 7.0 |

| Perennial ryegrass | Medium | 15 to 30 | 15 to 20 | 3/15 to 4/30 | 8/15 to 9/15 | ¼ to ½ | 2 to 4 | 5.5 to 7.0 |

| Prairiegrass | Medium | 30 to 40 | 25 | 2/1 to 4/1 | 8/15 to 9/15 | ¼ to ½ | 2 | 6.0 to 7.0 |

| Reed canarygrass | Medium to difficult | 8 to 12 | 8 | 3/15 to 4/30 | 8/15 to 9/15 | ¼ to ½ | 2 to 4 | 5.5 to 7.5 |

| Small grains | Easy | 100 to 130 | 90 to 110 | — | 9/1 to 10/15 | ¾ to 1 | 2 | 5.5 to 7.5 |

| Smooth bromegrass | Medium | 15 to 20 | 10 to 15 | 3/15 to 4/30 | 8/15 to 9/15 | ¼ to ½ | 4 | 5.5 to 7.0 |

| Tall fescue | Medium | 15 to 20 | 10 to 15 | 3/15 to 4/30 | 8/15 to 9/15 | ¼ | 3 to 6 | 5.5 to 7.0 |

| Timothy | Easy | 8 | 3 to 6 | 2/1 to 4/15 | 9/1 to 10/1 | ¼ to ½ | 2 to 4 | 5.5 to 7.5 |

| Warm-season grasses | ||||||||

| Bermudagrass (sprigged) | Medium | — | 25 to 30 bu/acre | 4/1 to 6/1 | — | 1 to 2 | 10 to 12 | 5.5 to 7.5 |

| Big bluestem | Medium to difficult | 8 | 6 | 4/15 to 5/31 | — | ¼ to ½ | 12 to 24 | 5.5 to 8.0 |

| Corn | Easy | — | 25,000 seeds/acre | 4/25 to 5/15 | — | 1 to 1½ | 2 to 3 | 5.5 to 7.0 |

| Crabgrass | Easy | 4 | 3 to 4 | 2/1 to 5/31 | — | ¼ to ½ | 1 to 2 | 5.5 to 8.0 |

| Eastern gamagrass | Difficult | — | 10 | 4/15 to 6/1 (Stratified seed) | 11/1 to 2/1 (Unstratified seed) | 1 to 1½ | 24 | 5.5 to 7.5 |

| Indiangrass | Medium to difficult | 8 | 6 | 4/15 to 5/31 | — | ¼ to ½ | 12 to 24 | 5.5 to 7.5 |

| Old World bluestem | Medium | 3 | 2 | 4/15 to 5/15 | — | ¼ to ½ | 4 to 6 | 5.5 to 7.0 |

| Pearlmillet | Easy | 20 to 30 | 15 | 5/1 to 6/15 | — | ½ to 1 | 2 | 5.5 to 7.5 |

| Sorhum-sundangrass | Easy | 30 to 35 | 20 to 25 | 5/1 to 6/30 | — | ½ to 1 | 2 | 5.5 to 8.0 |

| Switchgrass | Medium | 8 | 6 | 4/15 to 5/31 | — | ¼ to ½ | 12 to 16 | 5.5 to 7.5 |

| Legumes | ||||||||

| Alfalfa | Easy | 20 | 15 to 20 | 4/1 to 4/30 | 8/15 to 9/15 | ¼ to ½ | 2 to 4 | 6.5 |

| Birdsfoot trefoil | Medium | 6 to 8 | 5 | 2/1 to 4/1 | 8/15 to 9/15 | ¼ to ½ | 2 to 4 | 5.0 to 6.0 |

| Clover, alsike | Easy | 6 | 4 | 2/1 to 4/1 | 8/15 to 9/15 | ¼ | 2 to 4 | 5.5 to 7.0 |

| Clover, crimson | Easy | 25 | 20 | — | 8/15 to 9/15 | ¼ | 4 to 6 | 6.0 |

| Clover, kura | Difficult | 10 to 14 | 10 | 3/15 to 5/1 | — | ¼ | 18 to 24 | 6.0 |

| Clover, red | Easy | 8 | 6 | 2/1 to 4/30 | 8/15 to 9/15 | ¼ to ½ | 2 to 4 | 6.0 |

| Clover, white | Easy | 2 | 1 to 2 | 1/15 to 4/15 | 8/15 to 9/15 | ¼ to ½ | 2 to 4 | 6.0 |

| Hairy vetch | Medium | 30 to 35 | 25 to 30 | — | 9/1 to 11/15 | 1 | 4 to 6 | 5.5 to 7.0 |

| Lespedeza, annual | Medium | 15 | 10 | 2/1 to 4/15 | — | ¼ to ½ | 2 to 3 | 5.5 to 6.0 |

| Other | ||||||||

| Brassica species | Medium | — | 2 to 4 | 4/1 to5/13 | 8/15 to 9/15 | ¼ | 2 to 3 | 5.5 to 6.0 |

1Seeding rates on a pure live seed basis

This publication replaces Chapter 5, Selecting the Right Forage, in MU Extension publication M168, Dairy Grazing Manual. Original authors: Robert Kallenbach and Greg J. Bishop-Hurley, University of Missouri.