Pecans have been grown for commercial production in Missouri for more than 75 years. Approximately 12,000 acres of pecans are managed commercially in three areas of the state: southwest, southeast lowlands and central Missouri. More than 90 percent of these commercial trees are native varieties; however, about 38 percent of the trees grown by producers who grow improved or grafted varieties are nonnative.

Pecans in Missouri are noted for inconsistent production, and there are two reasons for this: alternate bearing and inadequate management of insect and disease pests. Growers can overcome these problems with better management techniques such as improved varieties, optimal tree spacing, irrigation, fertilization and pest management.

Nut losses from insects and diseases on pecans almost always are economical losses and can be severe enough to result in total crop failure. An integrated pest management (IPM) approach involves using resistant varieties, scouting and economic thresholds, pheromone traps and biological and synthetic pesticides to minimize losses. Spray recommendations in an IPM program represent a minimum level of pesticide input to control these pests while preserving beneficial insects and environmental quality.

This publication describes pecan insect pests and diseases that may cause economic losses to Missouri producers. Based on the findings of a four-year IPM program on pecans in southwest Missouri, first-generation pecan nut casebearer and pecan scab are the most economically damaging insect and disease, respectively.

Major pecan insect pests

In Missouri only five insect pests occur at high enough levels to cause economic losses: the pecan nut casebearer (PNC), hickory shuckworm (HSW), nut curculio (NC), pecan weevil (PW) and pecan phylloxera (PP).

In most years, however, only one or two of these pests will require treatment with an insecticide to reduce populations below economic thresholds. By carefully observing or scouting for these pests and using pheromone lures or other monitoring devices, pecan producers can save substantially on insecticide purchases. Spraying only when necessary also preserves beneficial insects that help keep many insect pests below economic thresholds.

Other insect pests that do not or rarely cause economic losses in Missouri pecan orchards are the fall webworm, walnut caterpillar and pecan spittlebug.

Pecan nut casebearer (Acrobasis nuxvorella)

Figure 1

Pecan nut casebearer larva boring into nut.

Life cycle

PNC overwinters as partially grown larvae in small cocoons (hibernacula) located at the junction of the bud and stem. Larvae leave the cocoons in the early spring about the time the buds open, feed briefly (about two weeks) on the exterior of opening buds and then bore into the young tender shoots, where they mature and pupate. In late May to early June, about the time that the pecan nuts are pollinated, the adult moths emerge and lay eggs on the young nuts, typically one per cluster. The eggs hatch three to nine days later. These first-generation larvae feed for a few days on the exterior of the buds, then migrate back to the nut clusters and bore into the nuts at the basal (stem) end. One larva can destroy from one to all of the nuts in the cluster (Figure 1). Infested nuts are held together by frass (waste) and silken threads cast out by the larvae. Larvae feed inside the nuts for three to four weeks, mature and pupate in one of the last nuts attacked, and the adults emerge nine to 14 days later.

Most second-generation moths emerge in mid-July. The second-generation larvae also attack nuts, but the loss is less because an individual PNC typically requires only one nut for its development. Third-generation moths emerge during late August and September, and larvae feed in the nut shuck at the base of the nut, on the shuck surface and, to some extent, on the leaves.

Description

Eggs are minute and change from white to pink as they incubate for three to nine days (an average of five days). Most are found near the flower end of the nut, on and beneath the calyx lobes. A larva has five pairs of prolegs and changes from olive-gray to gray-brown as it grows to measure one-half inch. The head is reddish-brown, and the body is sparsely covered with fine, white hairs. The larval stage lasts from 25 to 33 days. Adult moths are slate-gray with a ridge of long, dark scales on the basal end of forewings. Moths are one-third inch long, with a wingspan of four-fifths of an inch.

Scouting and control

The first generation is the most damaging, causing an average loss of 20 percent in unsprayed pecan orchards in southwest Missouri. Begin scouting for PNC eggs/larvae when all the catkins on native trees have fallen or when the tips of the nuts turn brown after pollination (approximately June 1 in southwest Missouri). You should inspect at least 200 nut clusters. When you find that 1 percent to 3 percent of the nut clusters have been damaged, apply an insecticide (Table 1). During years of heavy nut set on native trees, you can delay spraying until 5 percent of the nut clusters sustain PNC damage.

Table 1

Insecticides labeled for control of pecan nut casebearer (PNC), hickory shuckworm (HSW), pecan weevil (PW) and pecan phylloxera (PP).

| Active ingredient | Product name | Product rate1 | Target pests |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cypermethrin | Ammo 2.5 EC | 3 to 5 fluid ounces per acre | PNC, HSW, PW |

| Comments, special restrictions, wildlife cautions Pyrethroid. RESTRICTED USE. Toxic to fish and bees. Ground applications require a closed cab and protective equipment. Use lower rates for lower pest populations. Do not graze livestock in treated orchards. Do not apply within 21 days of harvest. |

|||

| Esfenvalerate | Asana XL | 4.8 to 14.5 fluid ounces per acre | PNC, HSW, PW, PP |

| Comments, special restrictions, wildlife cautions Pyrethroid. RESTRICTED USE. Toxic to fish and bees. Ground applications require a closed cab and protective equipment. Do not graze livestock in treated orchards. Do not apply within 21 days of harvest. |

|||

| Malathion | Cythion 5EC | 1 to 2 pints per acre | PNC, PP |

| Comments, special restrictions, wildlife cautions Organophosphate. RESTRICTED USE. Toxic to fish and bees. Ground applications require a closed cab and protective equipment. No preharvest interval. |

|||

| Bacillus thuringiensis, subsp. kurstaki | Javelin WG Dipel ES Vault WP |

0.75 to 1.25 pounds per acre 1 to 4 pints per acre 1 to 2.5 pounds per acre |

PNC |

| Comments, special restrictions, wildlife cautions Biological. Not toxic to beneficial insects, fish or humans. Significant precipitation 24 hours after application will reduce effectiveness. For best control make two applications seven days apart. Bt must be present at egg hatch for best control. |

|||

| Active ingredient | Product name | Product rate1 | Target pests |

| Chlorpyrifos | Lorsban 4E Lorsban 50W |

1.5 to 4 pints per acre 2 to 4 pints per acre 1 pound per 100 gallons 2 pounds per 100 gallons |

PNC, PP HSW PNC, PP HSW |

| Comments, special restrictions, wildlife cautions Organophosphate. Toxic to birds, fish, bees and other wildlife. Ground applications require a closed cab and protective equipment. Do not graze livestock in treated orchards. Do not apply within 28 days of harvest. |

|||

| Carbaryl | Sevin XLR Plus, 4F Sevin 80S Sevin 50W |

1 to 2.5 quarts pwe 100 gallons 1.25 to 3 pounds per acre 2 to 5 pounds per acre |

PNC, HSW, PW, PP |

| Comments, special restrictions, wildlife cautions Carbamate. Toxic to fish and bees. Overuse can lead to aphid outbreaks (due to reduction of natural enemies). Limit to two sequential applications a year. Ground applications require a closed cab and protective equipment. No preharvest interval. |

|||

| Endosulfan | Thiodan 3 EC Thiodan 50 WP |

1 quarts per 100 gallons 0.66 to 1 quarts per 100 gallons 1.5 pounds per 100 gallons 1 to 1.5 pounds per 100 gallons |

PNC PP PNC PP |

| Comments, special restrictions, wildlife cautions Chlorinated hydrocarbon. Toxic to birds, fish, bees and other wildlife. Ground applications require a closed cab and protective equipment. Do not graze livestock in treated orchards. |

|||

1Recommended rates refer to the amount of product per acre, or per 100 gallons of dilute spray in a conventional hydraulic-type sprayer. Spray gallonage will vary depending on tree size, density, planting distance, and stage of growth.

The narrow window of time for insecticide application is a two-day to four-day period that varies each year, so controlling the PNC can be difficult. Properly timing insecticide means applying it early enough to kill PNC larvae that have not yet begun boring into nutlets, but late enough to destroy late-dispersing egg-laying females and their offspring. A single, properly timed insecticide application will control PNC. The optimal application dates for PNC control ranged from June 15 to June 22 during our four-year study in southwest Missouri.

Texas researchers currently are field-testing traps that use a recently identified PNC female sex pheromone. The pheromone traps capture male PNC moths and serve as an early warning of adult flight activity. Trap monitoring can help you know when to begin scouting for eggs/larvae. Timely scouting allows you to more reliably assess the need for insecticide. The PNC pheromone traps should be on the market in 1996.

Hickory shuckworm (Cydia caryana)

Figure 2

Hickory shuckworm larva feeding inside pecan nut.

Life cycle

Three generations of HSW exist in southwest Missouri. Mature larvae overwinter in pecan shucks found on the ground or the tree and emerge as moths in mid-May. Spring development of HSW coincides with that of native hickory trees, which set fruit two to three weeks earlier than pecans. First-generation moths oviposit on hickory nuts, phylloxera galls and on pecan foliage, although those larvae hatching on pecan foliage rarely survive. Few pecan trees are infested with first-generation HSW because most moths die before pecan nut set. Second-generation larval feeding in the interior of the nut, which occurs from mid-July until shell hardening in mid-August, causes premature nut drop (Figure 2). In newly dropped nuts, you often can detect a chalky, white deposit at the larval entry point. This deposit is the scales of the female moth, placed to protect and seal the egg to the shuck. The HSW larva creates a paper-thin "window" in the shuck before pupation, which protects the pupa and provides an easily torn exit hole for the adult moth.

The third-generation moths typically emerge in early August. After shell hardening, the larvae mine tunnels in green shucks, which attaches the injured portions of the shucks to the shell (sticktights). Such third-generation shuckmining also delays nut maturity and inhibits proper kernel development.

Description

Eggs are minute, white and flattened and usually are laid on the shucks. Larvae have five pairs of prolegs, are creamy-white with brownish heads and are three-eighths of an inch long when mature. Adult moths are dark-gray nocturnal flyers, three-eighths of an inch long with a wingspread of one-half inch. Pupae, dark-brown and up to one-third inch long, are found within the shuck.

Scouting and control

Second-generation HSW rarely causes economic damage to native pecans. You should focus on controlling the third-generation moths, which often emerge at the same time as pecan weevils (early August). If PW emergence is delayed by drought conditions, you can apply an insecticide at the shell-hardening stage of nut development in mid-August. Adequate control of the third-generation often translates into lower HSW populations in subsequent years.

Nut curculio (Conotrachelus hicoriae)

Life cycle

The adult NC attacks immature pecans from mid-July to mid-August. Females make shallow, crescent-shaped punctures with their beaks in the shucks of immature nuts, and they deposit a single egg in each nut. The eggs hatch in four to five days, and the larvae feed for 10 to 14 days. This puncture and the larval feeding cause a bleeding of brown sap on the nut shuck at the point of entry and also premature nut drop. The damaged nuts drop from the tree in late July to late August, and the larvae continue to feed in the fallen nuts for about two more weeks. The larvae exit through a one-sixteenth inch hole and enter the soil. The adult NC emerges four weeks later, from September to October, and overwinters in ground trash or other protected places. The NC produces one generation a year and rarely is economically damaging.

Description

Adults are dark-gray to reddish-brown and are three-sixteenths of an inch long, with the beak about one-third the body length. Larvae have no legs or prolegs and are creamy-white, three-sixteenths of an inch long and found within immature pecans.

Scouting and control

People often confuse damage from the NC with that of the HSW. Usually trees adjacent to woody areas are prone to NC (and PW) attack because of the protection provided for overwintering sites. Insecticides applied for the control of third-generation HSW or PW also can reduce numbers of NC adults because their active periods coincide with these pests.

Pecan weevil (Curculio caryae)

Figure 3

Adult pecan weevil on a mature nut.

Life cycle

The adult PW typically emerges from the soil as early as July 25, frequently two to three days after a heavy rain. Adults cause two types of nut damage, depending on the stage of nut development during attack. Adults feeding on nuts before the gel stage (i.e., in the water stage, usually before shell hardening) induce kernel shriveling and blackening and premature nut drop. You sometimes can recognize nuts damaged in this way by a tiny, dark puncture that extends through the shuck and unhardened shell and a tobacco-like stain around the feeding wound. The presence of a larva in the nut, prior to shell hardening, indicates damage by another insect, usually NC or HSW. PW grubs are not found in nuts with unhardened shells.

The second type of nut damage is caused by weevil grubs feeding in partially matured nuts. Females oviposit two to four eggs in separate pockets within each kernel, after the nuts have entered the gel stage (about mid-August) until shuck split. Damaged mature nuts neither bleed nor drop. PW grubs feed on the kernels for approximately 30 days and then exit through a one-eighth of an inch emergence hole beginning in late September.

The PW remains in the larval stage for one to two years in earthen cells 4 to 12 inches underground. They pupate in early autumn and metamorphose into adults in about three weeks. These adults remain in the soil until the following August. The complete life cycle requires two to three years.

Description

Adults are light-brown to gray and about one-half inch long (Figure 3). The beak of the male is half the length of the body, and the beak of the female is slightly longer than the body. Larvae have no legs or prolegs and are creamy-white, C-shaped grubs with reddish-brown heads measuring up to one-half inch long.

Scouting and control

The PW is considered to be the most serious late-season pecan pest. Pecan varieties differ widely in their susceptibility to attack. Early ripening varieties that enter the gel stage in early August are most commonly infested. Ordinarily, weevils do not move far from the tree under which they emerge from the soil (provided there is a crop of nuts on that tree). Consequently, certain trees may be infested year after year while other adjacent trees of the same variety may not be attacked. You can spray pecan trees that have a history of PW damage with an insecticide at gel stage and then spray again 10 to 14 days later.

Cone-shaped emergence traps are the best way to detect first emergence of PW adults. Place the PW traps (four per tree, near the drip line) under suspected "weevil trees" by July 25. The economic threshold is five PW per trap when the nuts have reached the gel stage.

Pecan phylloxera (Phylloxera devastratrix)

Figure 4

Damage to foliage by pecan phylloxera.

Life cycle

Three species of phylloxera are pecan pests, but only the PP causes economic damage in certain years. The pecan leaf phylloxera and the southern pecan leaf phylloxera feed primarily on the foliage, whereas the PP attacks the foliage, shoots and fruit and is therefore the most damaging (Figure 4). The PP is a small, aphid-like insect that is rarely seen, but the galls it produces are prominent and easily noticed. Severe infestations cause malformed, weakened shoots that finally die; such infestations can destroy entire limbs.

The PP overwinters as eggs located inside the dead body of a female adult, which is in protected places on the branches of pecan trees. Soon after budbreak, the eggs hatch and the young insects migrate to opening buds or leaf tissue to feed on expanding new growth. The individuals that hatch from the overwintering eggs are known as stem mothers. Feeding by the stem mothers stimulates the development of galls, which enclose the stem mother in a few days. Inside the gall, the stem mother matures, lays her eggs and dies. Eggs laid by the stem mother hatch within the gall, and these nymphs feed within the gall until they mature.

In early July, the galls split open and the mature nymphs emerge as winged, asexual adults. These adults migrate to other trees or other parts of the same tree and lay eggs that are of two sizes. The smaller eggs hatch into male sexuals, and the larger eggs hatch into female sexuals. Male and female sexuals do not feed; their sole purpose is to mate and produce the overwintering egg. After mating, female sexuals seek out sheltered places on a tree, where they die with a fertilized egg inside them, protected for the winter.

Description

The adults and nymphs are small, one-eighth inch long, soft-bodied and cream-colored. They resemble aphids without cornicles (the protruding tubes located on the dorsal end of aphids). You'll need a hand lens to observe and identify them.

Scouting and control

Because the galls are seen easily, PP infestations often appear worse than they are. Only when galls occur on large numbers of shoots or nuts should you consider insecticides for the next season. Timing of control is critical, and you must target insecticide applications toward the stem mothers. Apply sprays from budbreak to one inch of new growth. Once the galls appear, it is too late to control PP for the season. Often only the trees that were infested the previous year will need treatment, not the entire orchard. Certain native trees and grafted varieties within an orchard become more heavily infested than other trees. Spraying or even removing these trees can prevent economic infestations from spreading throughout the entire orchard.

Major pecan diseases

Pecan scab (PS) is the only economic disease found in Missouri orchards. Nut losses on unsprayed susceptible varieties can reach 50 percent to 100 percent in a year. In addition, unsprayed trees prematurely defoliate, which negatively affects next season's nut crop. Two other diseases commonly seen on many varieties, but not at levels to cause economic losses, are anthracnose (Microspheara penicillata) on the nuts. Fungicides applied to control scab also control anthracnose and powdery mildew.

Pecan scab (Cladosporium caryigenum)

Life cycle

The scab fungus overwinters as a small, tight mat of fungal material called a "stroma" on shucks, leaf petioles and stems infected the previous season. With warmer temperatures and rainfall in the spring, fungal spores are produced on the stroma. Dew and rain spread spores locally within a tree, and the wind spreads them over long distances to adjacent trees or orchards.

Description

PS first appears as small, circular, olive-green spots that turn to black on the newly expanding leaves, leaf petioles and nut shuck tissue (Figures 5 and 6). All tissues are most susceptible when young and actively growing. Lesions expand and may coalesce. Old lesions crack and fall out of the leaf blade, giving a shot-hole appearance. Nut infections cause the greatest economic damage. Early infections may cause premature nut drop but more commonly cause the shuck to adhere to the nut surface, causing sticktights. Late infections can prevent nuts from fully expanding and decrease nut size.

Figure 5

Early scab infections on underside of leaf.

Figure 6

Severe scab infections on nuts. These nuts will drop prematurely or become sticktights.

Control

Resistant varieties offer the first line of defense against PS because pecan varieties vary greatly in their susceptibility to PS (Table 2). Some varieties are resistant, but many grafted varieties are susceptible. Producers should keep in mind that most commercial varieties were at one time resistant to PS and have now become susceptible because of genetic changes in fungus virulence. Native pecan trees in Missouri exhibit a high degree of genetic variability in resistance to scab. Some trees are resistant, but some are moderately susceptible. The grafted varieties 'Brewster,' 'Colby,' 'Giles,' 'Hirschi,' 'Neosho,' 'Osage,' 'Pawnee,' 'Peruque,' 'Ridgeway,' 'Shoal' and 'Stark's Hardy Giant' are susceptible to PS. 'Hirschi' is highly susceptible to PS and will be defoliated and suffer severe nut loss without protective fungicide sprays.

Table 2

Nut scab (Cladosporium caryigenum) severity ratings and resistance level of 24 pecan varieties in southwest Missouri.

| Variety | Severity1 rating | Resistance level |

|---|---|---|

| Barton | 1 | Resistant |

| Brewster | 5 | Susceptible |

| Chief | 1 | Resistant |

| Colby | 5 | Susceptible |

| Giles | 5 | Susceptible |

| Green River | 1 | Resistant |

| Grotjan Round | 3 | Moderately susceptible |

| Hirschi | 5 | Susceptible |

| Jenkins | 2 | Moderately resistant |

| Lad | 2 | Moderately resistant |

| McLeon | 1 | Resistant |

| Meramac | 3 | Moderately susceptible |

| Mohawk | 1 | Resistant |

| Native | 1 to 4 | Resistant to susceptible |

| Neosho | 5 | Susceptible |

| Norton | 1 | Resistant |

| Osage | 5 | Susceptible |

| Pawnee | 4 | Susceptible |

| Peruque | 4 | Susceptible |

| Posey | 1 | Resistant |

| Ridgeway | 4 | Susceptible |

| Shoal | 5 | Susceptible |

| Stark's Hardy Giant | 5 | Susceptible |

| Witte | 3 | Moderately susceptible |

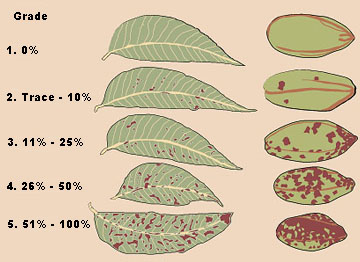

1Scab ratings based on Hunter-Roberts rating system. 1 = no lesions, 5 = 51-100 percent of shuck covered with lesions.

Tree spacing also can be effective in reducing scab severity on susceptible trees. Tight, compact canopies that restrict airflow and sunlight penetration favor scab infections because the foliage remains wet longer.

The most effective and accepted method of scab control on susceptible varieties is a preventive spray program with fungicides (Table 3). Early-season control is much more critical and economical than late-season control. In more humid environments typical of southern states, as many as eight or more sprays are required in a season.

Table 3

Fungicides labeled for control of pecan scab

| Active ingredient | Product name | Product rate1 |

|---|---|---|

| Triphenyltin hydroxide | Super Tin 4L Super Tin 80 WP |

6 to 12 fluid ounces 5 to 7.5 ounces |

| Comments, special restrictions, wildlife cautions Triphenyltin. RESTRICTED USE due to acute toxicity. Ground applications require a closed cab and protective equipment. Do not graze livestock in treated orchards. Also controls other nut and foliage diseases on pecans. |

||

| Benomyl | Benlate 50 WP | 0.5 to 1 pound |

| Comments, special restrictions, wildlife cautions Benzamidazole. Toxic to fish. Do not use Benlate alone. Tank mix at half-rate in combination with another non-benzamidazole fungicide. Use higher rates on trees more than 30 feet tall. Also controls other nut and foliage diseases on pecans. |

||

| Fenbuconazole | Enable 2F | 8 fluid ounces |

| Comments, special restrictions, wildlife cautions Sterol inhibitor. Toxic to fish. Do not apply after shuck split or within 28 days of harvest. Also controls other nut and foliage diseases on pecans. |

||

| Propiconazole | Orbit | 4 to 8 fluid ounces |

| Comments, special restrictions, wildlife cautions Sterol inhibitor. Toxic to fish. Apply 4 fluid ounces per acre as budbreak spray; higher rate needed to control scab on nuts. Ground applications require a closed cab and protective equipment. Do not graze livestock in treated orchards. Also controls other nut and foliage diseases on pecans. |

||

| Thiophanate methyl | Topsin M 70W Topsin M 85WDG Topsin M 4.5F |

0.5 to 1.0 pound 0.4 to 0.8 pound 10 to 20 fluid ounces |

| Comments, special restrictions, wildlife cautions Benzamidazole. Toxic to fish. Do not use Topsin M alone. Tank mix at half-rate in combination with another non-benzamidazole fungicide. Use higher rates on trees more than 30 feet tall. Also controls other nut and foliage diseases on pecans. |

||

1Recommended rates refer to the amount of product per acre. Spray gallonage will vary depending on tree size, density, planting distance and stage of growth.

In Missouri, however, you can achieve excellent control of PS on susceptible varieties with three sequential fungicide applications.

Apply the first spray (Orbit at 4 fluid ounces or Enable 2F at 8 fluid ounces) at three-fourths to one-inch growth after budbreak. Follow the first spray by two applications (of Super Tin 4L at 6 fluid ounces plus Benlate 50 WP or Topsin M 70W at 0.5 pound) at 14- to 21-day intervals.

On native trees or moderately susceptible cultivars, you often can delay the first fungicide spray until the first-generation PNC insecticide treatment and follow it by a second application 21 days later. The first spray is the most critical and often the most overlooked because the lesions are so small. However, remember that PS is difficult to control once infections of the foliage and young nuts occur.

Figure 7

The Hunter-Roberts System for evaluating pecan scab severity on leaves and nuts.