Editor's note

June 2013: The URLs for several resources on food defense have been updated. Download the PDF of the updated resources page.

The importance of food defense

Introduction

Food industry professionals see the U.S. food system as one of the safest in the world. However, the system’s image has blurred in the eyes of consumers as food safety recalls have been reported in the news media time and again.

Businesspeople in the food industry — from spinach growers watching sales plummet, to beef producers facing decreased demand, to restaurateurs and grocers working to maintain brand identities — know that protecting the food supply is of paramount importance. The food safety already practiced in the industry can minimize unintentional contamination in the food system. Protecting our food supply from intentional contamination, on the other hand, requires the practice of food defense strategies. Food defense is a relatively new but extremely important concept because of the many vulnerable access points in the farm-to-table food supply chain.

This guide explains the importance of food defense and the benefits of developing a food defense plan, as well as outlining how you can:

- Assess your operation’s vulnerabilities to intentional contamination

- Write a food defense plan detailing countermeasures to reduce the risk of intentional contamination

- Prepare a response plan for fast, efficient containment of an emergency

- Manage your food defense plan for t he long term.

Why food defense?

Based on an evaluation of critical infrastructures in the early 2000s, the federal government declared the food and agriculture sector to be one of 17 critical national infrastructures open to intentional attack (U.S. Department of Homeland Security, 2003). Even a mere threat to the food and agriculture sector could cause havoc within the food supply chain and have far-reaching consequences on the economy, human health and consumer confidence.

In military lingo, the U.S. food industry is considered a “soft” target because it is under-defended and could be overcome from many directions. Not only is it large and geographically dispersed, but it also comprises many different types and scales of operation across the country. Plus, the food industry employs almost one-fifth of our population and produces more than one-tenth of our gross domestic product. And most importantly, everyone must eat!

Threats to this foundational aspect of our everyday life have the potential to cause a great deal of harm, such as:

Threats to this foundational aspect of our everyday life have the potential to cause a great deal of harm, such as:

- Physical

Depending on the contaminant or where it’s used, people or livestock could sicken or even die. - Economic

Direct costs resulting from an intentional contamination could include medical costs, lost wages for unemployed workers, quarantines of infected humans and livestock or containment of food products, decontamination of facilities and products, and disposal of carcasses or products. Indirect costs could include production down time, government compensation to producers for feed costs or livestock, and loss of suppliers or customers. An intentional contamination event could even affect international trade, causing U.S. producers to lose billions of dollars. - Psychological

Intentional contamination could cause a loss of consumer confidence in a particular product or commodity, such as the rejection of spinach after the discovery of E. coli, or even a panic among consumers. - Political

A widespread, severe contaminant could potentially cause political unrest.

Who would intentionally contaminate the food system?

Clearly, the food industry is a potential place to wreak havoc. But what kind of person or group would try to contaminate our food supply, and why?

Many people immediately assume that intentional contamination is caused mainly by groups dissatisfied with how our food is produced. However, intentional contamination may be caused not only by people outside an operation but also by workers, family members or others with regular access, and most cases have occurred for more mundane reasons than ideology.

Disgruntled workers: Employees often must have access to many different areas of an operation in order to do their jobs effectively. When the relationship between a worker and employer goes bad, however, a disgruntled worker may decide to contaminate the livestock or food products in the operation to embarrass the boss (Example 1) or company, or to cause as much economic damage as possible.

Shady business practices: Intentional contamination can also be caused by cutting corners to save money or other shady business practices. One of the largest recalls in the mid-2000s, of pet food containing melamine (Example 2), was caused by a manufacturer seeking to provide the lowest-cost product on the market that still met quality standards, in this case by fraudulent means. Although the aim of those trying to reduce costs by using inferior or fraudulent ingredients isn’t to cause economic harm or disrupt society but just to save a buck, the results can still be far reaching.

Emotional stress: How a worker will behave in a stressful situation is difficult to predict. Even your most-trusted employees, including family members, may do or say things that are out of character at stressful moments in their lives. A worker may intentionally contaminate the food supply in a misguided response to an emotionally stressful situation, such as the love triangle described in Example 3.

Political ideology: As mentioned above, our first thoughts about intentional contamination are often about groups who may contaminate the food supply for ideological reasons, such as protesting the exploitation of animals, or to cause economic harm or physical disruption of daily life. As described in Example 4, groups may also contaminate the food supply for political reasons.

Who is responsible for defending the food supply?

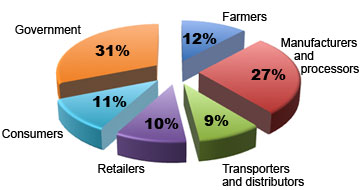

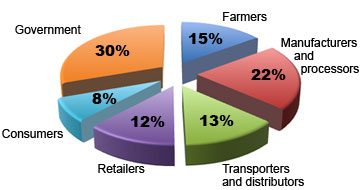

When the food supply is threatened, contaminated or disrupted, consumers tend to blame producers and manufacturers. Data collected by researchers at the University of Minnesota show that the public holds government and the food industry most responsible for protecting the food supply (Figure 1) and for picking up the tab for food defense (Figure 2) (Stinson et al., 2008). Consumers assume their food is safe when they buy it and aren’t willing to pay extra for something they believe should be standard.

Perhaps more distressing for the food industry is that consumers are losing confidence in the safety of the food system. According to the University of Minnesota study, between 2005 and 2007, a period of several major food recalls, the number of consumers who were very confident in the safety of the food supply decreased and the number of consumers who were not very confident increased.

Figure 1

Who do consumers believe is responsible for food defense?

Figure 2

Who do consumers believe is responsible for paying for food defense?