Writer

Linda GeistWEST PLAINS, Mo. – Southwest Missouri farmers and livestock producers are no strangers to drought. In 2022, livestock owners face short-term and long-term challenges growing pastures for grazing and winter feeding.

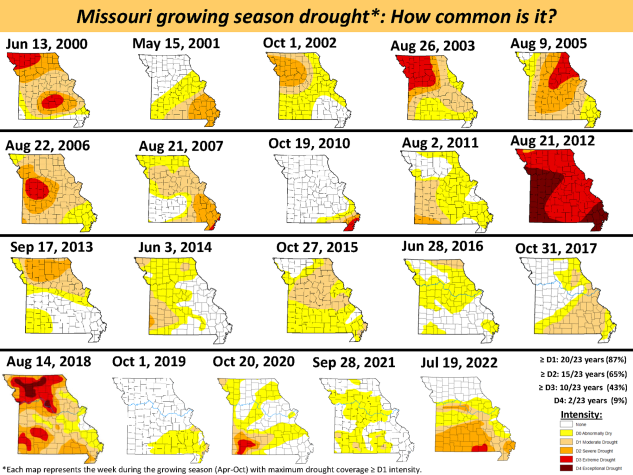

According to the U.S. Drought Monitor, Missouri has seen droughts of level D1 or higher in 20 of the last 23 years. In 10 of those years, parts of Missouri experienced D3 (extreme) drought. Two of the last 23 years—2012 and 2018—saw D4 (exceptional) drought, says University of Missouri Extension agronomist Sarah Kenyon. The worst was 2012, when almost all of Missouri experienced D3 or D4 drought.

This year, drought began developing in pockets of southeastern Missouri in June, Kenyon says. By June 28, more than half of the state suffered from lack of precipitation. By July 21, drought blanketed Missouri south of Interstate 70, with intense drought in southwestern, south-central and southeastern Missouri.

Forages responded with weakened stands, thin pastures and lower supplies, leaving producers scrambling for ways to feed livestock, Kenyon says.

Expect more weeds next year, she says. However, many “dead” pastures may recover. How pastures recover depends largely upon the stand’s health and vigor before drought.

Researchers at the University of Kentucky compared orchard grass pastures and found rotational grazing pastures fared far better than pastures under continuous grazing.

Graze plants no lower than 2 inches during drought. This allows plants to regrow and prevents animals from ingesting the highest concentrations of toxins located in fescue’s lower 2 inches.

After drought, pastures may require slightly longer to recover. Consider lower stocking rates, but don’t compromise forage quality, says Kenyon.

Pastures are best to graze again when plants develop three or four leaves or are 6-10 inches tall.

Growers may set aside a “sacrifice” paddock to allow other paddocks to rest.

One short-term drought option is to plant an emergency crop from August to early October. Kenyon recommends brassica, small grains, ryegrass and stockpile fescue.

Brassica forages such as turnips, radishes and kale grow rapidly and continue to grow after frost. Bulbs below ground may also be consumed by livestock. However, limit this forage in the total diet to avoid bloat and other digestive issues. Plant brassicas in August and apply 75 pounds per acre of nitrogen at planting. Graze as short as possible and start early. Finish grazing by Jan. 1.

Plant small grains early; begin grazing by early November and end by mid-March. Kenyon recommends a split application of nitrogen. Well-rooted and tillered plants offer grazing six to eight weeks after planting. Too-short grazing may cause winterkill.

Most farmers plant spring oats in March or April, but they can be planted in August. With moisture, livestock can graze oats six to eight weeks after planting. Oats are not drought-tolerant and do not produce good stands under dry conditions. Kenyon recommends planting 2-3 bushels per acre and applying 30-60 pounds of nitrogen per acre.

If planted for grazing, plant wheat in August. Plant at higher seeding rates to allow for pest problems. Apply 30-50 pounds of nitrogen.

Cereal rye establishes quickly in fall. The later the planting date, the more rye becomes the best option. Hardy in drought, heat and poor soil conditions, it also is less subject to winterkill than other options. It produces more winter pasture than oats, and cows gain nearly double the pounds per acre on cereal rye than on oats.

Triticale, a cross between wheat and rye, offers wheat’s quality and rye’s toughness. Barley must be planted early but loses foliage to winterkill, limiting spring grazing. Rotational grazing is the best use of annual ryegrass. It is a good fit for thin tall fescue stands.

Other recommendations from Kenyon:

• Plant a winter-hardy cultivar of annual ryegrass in late August at 25-30 pounds per acre with 50 pounds of nitrogen at planting. Apply another 50 pounds of nitrogen in late February. Begin grazing when grass reaches 8-10 inches. Leave 3-4 inches of stubble for regrowth. If reseeding, remove livestock in mid-May.

• Plant small grains August to early October at 100-130 pounds per acre. Apply 50-75 pounds of nitrogen at planting and add 50 more pounds in spring if needed. Do not graze at less than 3 inches. Graze heavily in the spring.

Long-term drought options:

• To thicken stands, interseed tall fescue, orchard grass, brome and others in late August to early October. Interseed clover and/or annual lespedeza in February. Plant warm-season grasses in mid-May in 10%-25% of total grazing acres. Warm-season grasses tolerate hot, dry weather best.

Consider pasture herbicide residuals, which can kill new stands of grass and legumes, says Kenyon. Consider burndown herbicide options before establishment. After establishment, grass should be well-tillered and established before using common pasture herbicides.

More information forage producers is available from the Alliance for Grassland Renewal at www.grasslandrenewal.org. The alliance includes partners from university, government, industry and nonprofit groups.

Drought resources from MU Extension: mizzou.us/DroughtResources.

Drought resources from MU Integrated Pest Management: ipm.missouri.edu/drought.

Graphic:

https://extension.missouri.edu/media/wysiwyg/Extensiondata/NewsAdmin/Photos/2022/20220803-drought-1.png

Missouri has seen droughts in 20 of the last 23 years. Graphic courtesy Pat Guinan.